In some applications, the applicant seeks to register a "phantom" element (i.e., a word, alpha-numeric designation, or other component that is subject to change) as part of a mark. The applicant represents the changeable or "phantom" element by inserting a blank, or by using dots, dashes, underlining, or a designation such as "XXXX."

Examples include marks incorporating a date (usually a year), a geographic location, or a model number that is subject to change. While these are some of the most common examples of the types of elements involved, there are many variations.

If an application seeks registration of a mark with a significant changeable or "phantom" element, the examining attorney must consider whether the element encompasses so many potential combinations that the drawing would not give adequate constructive notice to third parties as to the nature of the mark and a thorough and effective search for conflicting marks is not possible. If so, the examining attorney must refuse registration under §§1 and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051 and 1127, on the ground that the application seeks registration of more than one mark. See In re Int'l Flavors & Fragrances Inc., 183 F.3d 1361, 51 USPQ2d 1513 (Fed. Cir. 1999); In re Soc’y of Health & Physical Educators, 127 USPQ2d 1584 (TTAB 2018); In re Constr. Research & Tech. GmbH, 122 USPQ2d 1583 (TTAB 2017); In re Primo Water Corp., 87 USPQ2d 1376 (TTAB 2008) ; see also TMEP §807.01 (regarding the requirement that an application be limited to one mark).

In International Flavors, the applicant filed three applications to register the designations "LIVING xxxx," "LIVING xxxx FLAVOR," and "LIVING xxxx FLAVORS," for essential oils and flavor substances. The applications indicated that "the ‘xxxx’ served to denote 'a specific herb, fruit, plant or vegetable.'" Int’l Flavors, 183 F.3d at 1363-64, 51 USPQ2d at 1514-15. In upholding the refusal of registration, the Federal Circuit noted that under §22 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1072, registration serves as constructive notice to the public of the registrant’s ownership of the mark and, therefore, precludes another user from claiming innocent misappropriation as a trademark infringement defense. To make this constructive notice meaningful, the mark as registered must accurately reflect the mark that is used in commerce, so that someone who searches the register for a similar mark will locate the registration. The court stated that "phantom marks" with missing elements "encompass too many combinations and permutations to make a thorough and effective search possible" and, therefore, the registration of these marks does not provide adequate notice to competitors and the public. Id. at 1367-68, 51 USPQ2d at 1517-18.

In Soc’y of Health & Physical Educators, the Board affirmed a refusal of the standard-character mark SHAPE XXX, in which "XXX" was intended to denote "the unabbreviated name of a state of the United States and Puerto Rico." In re Soc’y of Health & Physical Educators, 127 USPQ2d at 1585. The Board noted that the registrability of a mark with a variable element depends on "whether the permutations of the variable element affect the commercial impression so as to result in more than one mark." Id. at 1587. Thus, for such a mark to register, the "the possible variations of the mark must be legal equivalents." Id. The Board found that, while the variable element in the applied-for mark was geographically descriptive, it nonetheless "alters the characteristics of the purported mark SHAPE XXXX, resulting in the commercial impression of multiple marks" and that "[t]he differences in the variable elements are more than minor variations or inconsequential modifications of the basic mark." Id. at 1589 (noting that the variable terms have different meanings, sounds, and appearances, and may also acquire distinctiveness). Accordingly, the Board determined that "the different permutations of SHAPE XXXX are not legal equivalents" and therefore the mark comprised more than one mark. Id. at 1588, 1590.

In Primo Water, the Board affirmed a refusal of registration of a mark comprising the "placement and orientation of identical spaced indicia" on either side of the handle of a water bottle in inverted orientation, where the description of the mark indicated that the "indicia" can be "text, graphics or a combination of both." Primo Water, 87 USPQ2d at 1377. The Board noted that the varying indicia must be viewed by consumers before they can perceive the repetition and inversion elements of the mark, and that marks with changeable or "phantom" elements do not provide proper notice to other trademark users. Id. at 1379-80. The Board also noted that the only issue on appeal was whether applicant seeks to register more than one mark, and that this issue is separate from the question of whether the proposed mark is distinctive and functions as a mark. Id. at 1380; see also In re Upper Deck Co., 59 USPQ2d 1688, 1691 (TTAB 2001) (finding hologram used on trading cards in varying shapes, sizes, contents, and positions constitutes more than one "device" as contemplated by §45 of the Trademark Act).

A mark with a changeable element may be registrable if the element is limited in terms of the number of possible variations, such that the drawing provides adequate notice as to the nature of the mark and an effective §2(d) search is possible. Cf. In re Dial-A-Mattress Operating Corp., 240 F.3d 1341, 1347-48, 57 USPQ2d 1807, 1812-13 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (rejecting the argument that the mark (212) M-A-T-T-R-E-S is an unregistrable phantom mark, because, although 212 was displayed in dotted lines to indicate it was a changeable element, it was clear that this element was "an area code, the possibilities of which are limited by the offerings of the telephone companies"). For example, a "phantom mark" refusal would not be necessary for the mark T.MARKEY TRADEMARK EXHIBITION 2***, in which the asterisks represent elements that change to indicate different years. However, if the changeable element’s potential significance and range of meanings is not readily clear from the context, and thus the public would be unable to determine scope of any resulting registration, refusal is appropriate. See In re Constr. Research & Tech. GmbH, 122 USPQ2d at 1586 (affirming a "phantom mark" refusal of the marks NP - - - and SL - - -, in which "- - -" represented up to three numeric digits, noting that the missing information in the marks is potentially wide-ranging and subject to different interpretations depending on the context).

See TMEP §807.01 regarding the requirement that an application be limited to one mark.

The examining attorney must also consider whether the "phantom mark" is a substantially exact representation of the mark as used on the specimen in a use-based application, or the mark in the home country registration in an application based on Trademark Act §44, 15 U.S.C. §1126. See TMEP §§807.12–807.12(e).

The applicant may amend the mark to overcome a refusal on the ground that the mark on the drawing does not agree with the mark as used on the specimen, or with the mark in the foreign registration, if the amendment is not a material alteration of the mark. See TMEP §§807.14–807.14(f) regarding material alteration.

In an intent-to-use application for which no allegation of use has been filed, it may be unclear whether the applicant is seeking registration of a mark with a changeable element. In that case, the examining attorney should advise the applicant that, if the specimen filed with an amendment to allege use under §1(c) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1051(c), or a statement of use under §1(d) of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1051(d), shows that applicant is seeking registration of a mark with a changeable element, registration may be refused on the ground that the application seeks registration of more than one mark. This is done strictly as a courtesy. If information regarding this possible ground for refusal is not provided before the applicant files an allegation of use, the USPTO is not precluded from refusing registration on this basis.

Otherwise, if it is clear that the applicant is seeking registration of a "phantom mark" (e.g., if the application includes a statement that "the blank line represents matter that is subject to change") that would not provide adequate constructive notice of the nature of the mark and that precludes a thorough and effective search for conflicting marks (see TMEP §1214.02), the examining attorney should issue a refusal of registration under §§1 and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051 and 1127, on the ground that the application seeks registration of more than one mark.

The "phantom mark" refusal may be issued in applications under §§44 and 66(a) as well as §1 of the Trademark Act.

A domain name is part of a Uniform Resource Locator ("URL"), which is the address of a site or document on the Internet. A domain name is usually preceded in a URL by "http://www." The "http://" refers to the protocol used to transfer information, and the "www" refers to World Wide Web, a graphical hypermedia interface for viewing and exchanging information.

In general, a domain name is comprised of a second-level domain, a "dot," and a top-level domain ("TLD"). The wording to the left of the "dot" is the second-level domain. A TLD is the string of letters that follows the last "." or "dot".

Example: If the domain name is "ABC.com," the term "ABC" is a second-level domain and the term "com" is a TLD.

Generic TLDs. If a TLD has three or more characters, it is known as a "generic top-level domain" or "gTLD." The following are examples of gTLDs designated for use by the public:

|

.com |

commercial, for-profit organizations |

|

.edu |

4-year, degree-granting colleges/universities |

|

.gov |

U.S. federal government agencies |

|

.int |

international organizations |

|

.mil |

U.S. military organizations, even if located outside the U.S. |

|

.net |

network infrastructure machines and organizations |

|

.org |

miscellaneous, usually non-profit organizations and individuals |

Each of the gTLDs listed above is intended for use by a certain type of organization. For example, the gTLD ".com" is for use by commercial, for-profit organizations. However, the administrator of the .com, .net, .org, and .edu gTLDs does not check the requests of parties seeking domain names to ensure that such parties are a type of organization that should be using those gTLDs. On the other hand, .mil, .gov, and .int gTLD applications are checked, and only the U.S. military, the U.S. government, or international organizations are allowed in the respective domain space.

Country-Code TLDs. Country-code TLDs are for use by each individual country. For example, the TLD ".ca" is for use by Canada, and the TLD ".jp" is for use by Japan. Each country determines who may use its code. For example, some countries require that users of their code be citizens or have some association with the country, while other countries do not.

See www.icann.org and TMEP §§1215.02(d)(i)─1215.02(d)(iv) for additional information about other gTLDs and TMEP §1209.03(m) about descriptiveness or genericness of marks comprising domain names.

Generally, when a trademark, service mark, collective mark, or certification mark is composed, in whole or in part, of a domain name, neither the beginning of the URL ("http://www.") nor the gTLD has any source-indicating significance. Instead, those designations are merely devices that every Internet site provider must use as part of its address. Advertisements for all types of products and services routinely include a URL for the website of the advertiser, and the average person familiar with the Internet recognizes the format for a domain name and understands that "http," "www," and a gTLD are a part of every URL.

However, in 2011, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) authorized the launch of a program to introduce new gTLDs. Some of the gTLDs under consideration may have significance as source identifiers. To the extent that some of the new gTLDs under consideration comprise existing registered trademarks or service marks that are already strong source identifiers in other fields of use, some of the premises mentioned above may no longer hold true for such gTLDs (e.g., a gTLD consisting of a coined mark is not an abbreviation of an entity type or class of intended user of domain space). Where the wording following the "." or "dot" is already used as a trademark or service mark, the appearance of such marks as a gTLD may not negate the consumer perception of them as source indicators. Accordingly, in some circumstances, a gTLD may have source-indicating significance. See TMEP §1215.02(d)─1215.02(d)(iv) (mark consisting of a gTLD for domain registry operator and domain name registrar services, where the wording following the "." or "dot" is already used as a trademark or service mark, may be registrable).

A mark composed of a domain name is registrable as a trademark or service mark only if it functions as a source identifier. The mark, as depicted on the specimen, must be presented in a manner that will be perceived by potential purchasers to indicate source and not as merely an informational indication of the domain name address used to access a website. See In re Roberts, 87 USPQ2d 1474, 1479 (TTAB 2008) (finding that irestmycase did not function as a mark for legal services, where it is used only as part of an address by means of which one may reach applicant’s website, or along with applicant’s other contact information on letterhead); In re Eilberg, 49 USPQ2d 1955, 1957 (TTAB 1998) .

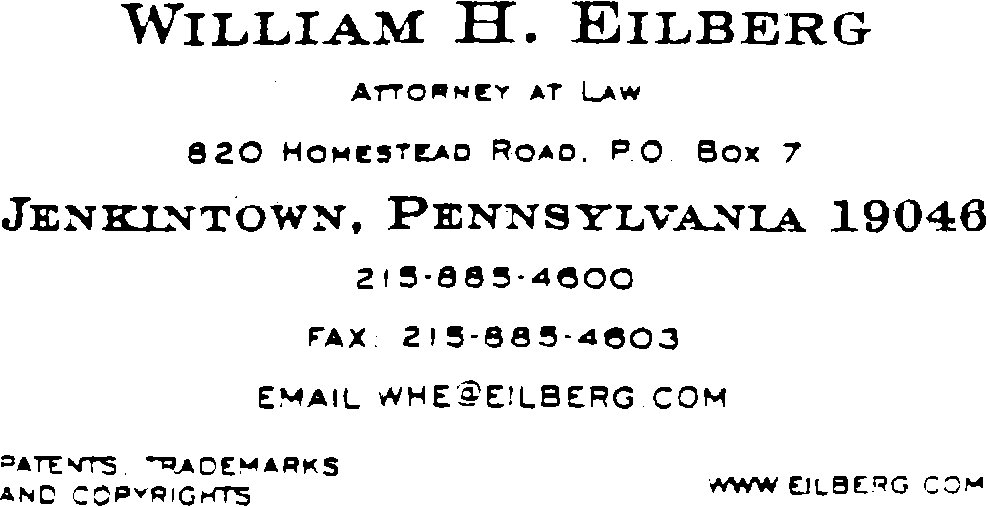

In Eilberg, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board held that a term that only serves to identify the applicant’s domain name or the location on the Internet where the applicant’s website appears, and does not separately identify applicant’s services, does not function as a service mark. The applicant’s proposed mark was WWW.EILBERG.COM, and the specimen showed that the mark was used on letterhead and business cards in the following manner:

(The specimen submitted was the business card of William H. Eilberg, Attorney at Law, 820 Homestead Road, P.O. Box 7, Jenkintown, Pennsylvania 19046, 215-855-4600, email whe@eilberg.com.)

The Board affirmed the examining attorney’s refusal of registration on the ground that the matter presented for registration did not function as a mark, stating that:

[T]he asserted mark, as displayed on applicant’s letterhead, does not function as a service mark identifying and distinguishing applicant’s legal services and, as presented, is not capable of doing so. As shown, the asserted mark identifies applicant’s Internet domain name, by use of which one can access applicant’s Web site. In other words, the asserted mark WWW.EILBERG.COM merely indicates the location on the Internet where applicant’s Web site appears. It does not separately identify applicant’s legal services as such. Cf. In re The Signal Companies, Inc., 228 USPQ 956 (TTAB 1986).

This is not to say that, if used appropriately, the asserted mark or portions thereof may not be trademarks or [service marks]. For example, if applicant’s law firm name were, say, EILBERG.COM and were presented prominently on applicant’s letterheads and business cards as the name under which applicant was rendering its legal services, then that mark may well be registrable.

Eilberg, 49 USPQ2d at 1957.

The examining attorney must review the specimen in order to determine how the proposed mark is actually used. It is the perception of the ordinary customer that determines whether the asserted mark functions as a mark, not the applicant’s intent, hope, or expectation that it does so. See In re The Standard Oil Co., 275 F.2d 945, 947, 125 USPQ 227, 229 (C.C.P.A. 1960) .

If the proposed mark is used in a way that would be perceived as nothing more than an Internet address where the applicant can be contacted, registration must be refused. Examples of a domain name used only as an Internet address include a domain name used in close proximity to language referring to the domain name as an address, or a domain name displayed merely as part of the information on how to contact the applicant.

Example: The mark is WWW.ABC.COM for online ordering services in the field of clothing. A specimen consisting of an advertisement that states "visit us on the web at www.ABC.com" does not show service mark use of the proposed mark.

Example: The mark is ABC.COM for financial consulting services. A specimen consisting of a business card that refers to the services and lists a telephone number, fax number, and the domain name sought to be registered does not show service mark use of the proposed mark.

If the specimen fails to show use of the domain name as a mark and the applicant seeks registration on the Principal Register, the examining attorney must refuse registration on the ground that the matter presented for registration does not function as a mark. The statutory bases for the refusals are §§1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, and 1127, for trademarks; and §§1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1053, and 1127, for service marks.

If the applicant seeks registration on the Supplemental Register, the examining attorney must refuse registration under Trademark Act §23, 15 U.S.C. §1091.

Advertising one’s own products or services is not a "service" under the Trademark Act. In re Reichhold Chems., Inc., 167 USPQ 376 (TTAB 1970) . See TMEP §§1301.01(a)(ii) and 1301.01(b)(i). Therefore, businesses that create a website for the sole purpose of advertising their own products or services cannot register a domain name used to identify that activity. In examination, the issue usually arises when the applicant describes the activity as a registrable service, e.g., "providing information about [a particular field]," but the specimen of use makes it clear that the website merely advertises the applicant’s own products or services. In this situation, the examining attorney must refuse registration because the mark is used to identify an activity that does not constitute a "service" within the meaning of the Trademark Act. The statutory basis for the refusal is Trademark Act §§1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1053, and 1127.

In viewing a domain name mark (e.g., ABC.COM or HTTP://WWW.ABC.COM), consumers generally look to the second-level domain name for source identification, not to the generic top-level domain (gTLD) or the terms "http://www." or "www." Therefore, it is usually acceptable to depict only the second-level domain name on the drawing page, even if the specimen shows a mark that includes a traditional gTLD (such as .COM) or the terms "http://www." or "www." However, if the mark depicted in the specimen includes a gTLD that serves a source-indicating function, the drawing of record must include such source-indicating gTLD. Cf. Institut Nat’l des Appellations D’Origine v. Vintners Int’l Co., 958 F.2d 1574, 22 USPQ2d 1190 (Fed. Cir. 1992) (CHABLIS WITH A TWIST held to be registrable separately from CALIFORNIA CHABLIS WITH A TWIST as shown on labels); In re Raychem Corp., 12 USPQ2d 1399 (TTAB 1989) (refusal to register TINEL-LOCK based on specimen showing "TRO6AI-TINEL-LOCK-RING" reversed). See also 37 C.F.R. §2.51(a)–(b), and TMEP §§807.12–807.12(e).

Example: The specimen shows the mark HTTP://WWW.ABC.COM. The applicant may elect to depict only the term "ABC" on the drawing.

Sometimes the specimen fails to show the entire mark sought to be registered (e.g., the drawing of the mark is HTTP://WWW.ABC.COM, but the specimen only shows ABC). If the drawing of the mark includes a gTLD, or the terms "http://www." or "www.," the specimen must also show the mark used with these terms. Trademark Act §1(a)(3)(C), 15 U.S.C. §1051(a)(3)(C).

Example: If the drawing of the mark is ABC.COM, a specimen that only shows the term ABC is unacceptable.

If, in an application in which the identification of services specifies or otherwise encompasses domain registry operator or domain name registrar services, and the applied-for mark consists of or includes wording without a dot (".") before it, but the specimen provided shows use of the mark only with a "." before the wording, or vice versa, the examining attorney must refuse the specimen on the grounds that the marks do not match because the commercial impression created by the applied-for mark differs from the commercial impression created by the mark shown in the specimen. Specifically, when used in connection with domain registry operator or domain name registrar services, wording immediately preceded by a "." will likely be viewed by consumers as a generic top-level domain (gTLD). On the other hand, the same wording, used in connection with the same services, but shown without the "." would not give the impression of a gTLD and could be viewed as an indicator of source, such that the commercial impression created by the marks materially differs. Thus, in this context, the "."does not constitute the type of "extraneous, nondistinctive punctuation" discussed in TMEP §807.12(a)(i) and the drawing may not be amended to add a "." to, or delete a "." from, the mark. See TMEP §1215.08(c).

Example: If the applied-for mark is TMARKIE for "domain-name registration services," a specimen that shows the mark as .TMARKIE is unacceptable.

See TMEP §§807.14–807.14(f) and 1215.08–1215.08(b) regarding material alteration.

Background. A "registry operator" maintains the master database of all domain names registered in each top-level domain (TLD), and also generates the "zone file," which allows computers to route Internet traffic to and from TLDs anywhere in the world. A "registrar" is an entity through which domain names may be registered, and which is responsible for keeping website contact information records and submitting the technical information to a central directory known as the "registry." The terms "registry operator" and "registrar" refer to distinct activities and are not interchangeable. Further, "registry operators" and "registrars" are distinguishable from re-sellers, which are entities that are authorized by registrars to sell or register particular Internet addresses on a given TLD. See Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), Acronyms and Terms, https://www.icann.org/en/icann-acronyms-and-terms?nav-letter=a&page=1 (accessed Nov. 30, 2022).

Failure to function refusal. A mark composed solely of a generic TLD (gTLD) for domain registry operator or domain name registrar services typically fails to function as a mark because consumers are predisposed to perceive gTLDs as merely a portion of a web address rather than as an indicator of the source of domain registry operator and domain name registrar services. See In re Vox Populi Registry Ltd., 2020 USPQ2d 11289, at *3-4 (TTAB 2020) (citing In re AC Webconnecting Holding B.V., 2020 USPQ2d 11048, at *3-4 (TTAB 2020)), aff'd, 25 F.4th 1348, 2022 USPQ2d 115 (Fed. Cir. 2022); TMEP §1215.02. For any proposed mark, including a gTLD, the determination of whether the designation functions as a mark hinges on consumer perception. In re Vox Populi Registry Ltd., 25 F.4th 1348, 1351, 2022 USPQ2d 115, at *2 (Fed. Cir. 2022); In re AC Webconnecting Holding B.V., 2020 USPQ2d 11048, at *3. Therefore, registration on the Principal Register of such proposed marks must initially be refused under Trademark Act §§1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1053, and 1127, on the ground that the gTLD does not function as a mark to identify and distinguish the source of the services because it would not be perceived as a mark. TMEP §1301.02(a). For applications on the Supplemental Register, the refusal must be made under Trademark Act §§23(c) and 45, 15 U.S.C §§1091(c), 1127.

Including stylization in a gTLD does not render it registrable on the Principal Register unless the stylization creates a commercial impression separate and apart from the impression made by the wording itself. In re Vox Populi Registry, 25 F.4th at 1353, 2022 USPQ2d 115, at *4; In re Cordua Rests., Inc., 823 F.3d 594, 606, 118 USPQ2d 1632, 1639-40 (Fed. Cir. 2016). In addition, a "completely ordinary and nondistinctive" stylized display of a gTLD does not render it registrable on the Supplemental Register. In re AC Webconnecting Holding B.V., 2020 USPQ2d 11048, at *13-14 (citing In re Anchor Hocking Corp., 223 USPQ 85, 88 (TTAB 1984)). See TMEP §1209.03(w) regarding stylization of descriptive or generic wording.

Response options. The applicant may, in some circumstances, avoid or overcome the refusal by providing evidence that the mark will be perceived by consumers as a source identifier. In addition to such evidence, the applicant must show that: (1) it has entered into a currently valid Registry Agreement with ICANN designating the applicant as the Registry Operator for the gTLD identified by the mark and (2) the identified services will be primarily for the benefit of others.

Descriptiveness refusal. If the gTLD merely describes the subject or user of the domain space, the examining attorney must also refuse registration under Trademark Act §2(e)(1), 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(1), on the ground that the gTLD is merely descriptive of the registry services. See TMEP §§1209-1209.03(w) regarding refusals based on descriptiveness.

Relevant evidence that the gTLD shown in the mark may be perceived as a source identifier includes evidence that the gTLD is the subject of one or more prior U.S. registrations for goods/services that are related to the identified subject matter of the websites to be registered via the domain registry operator and domain name registrar services. Applicants seeking to demonstrate that a gTLD functions as a mark by relying on prior U.S. registration(s) must establish:

The prior U.S. registration(s) must show the same mark as that shown in the relevant application. However, the lack of a "." or "dot" in the prior U.S. registration(s) is not determinative as to whether the mark in the registration is the same as the mark in the application. In addition, the prior registration may be registered pursuant to §2(f) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(f).

Because a consumer’s ability to recognize a gTLD in an application as a source-identifying mark is based, in part, on the applicant’s prior registration(s) for the same mark, the applicant must limit the "field of use" for the identified domain registry operator and domain name registrar services to fields that are related to the goods/services listed in the submitted prior registration(s). For example, if the applicant submits prior registrations identifying its goods as "automobiles," the services in the application may be identified as "domain name registrar services for websites featuring automobiles." However, the applicant may not identify its services as, for example, "domain name registrar services for websites featuring restaurants" or merely as "domain name registrar services."

If the applicant does not specify a field of use for the identified domain registry operator and domain name registrar services, or specifies a field of use that includes goods/services not listed in the prior registration(s), the examining attorney must require the applicant to amend the identification of services so as to indicate only a field of use that is related to goods/services that are the subject of the prior registration(s). In amending the identification, the applicant may not broaden its scope. 37 C.F.R. §2.71(a); TMEP §§1402.06–1402.06(b).

If the application is not amended, or cannot be amended, to specify a field of use that is related to the goods/services listed in the prior registration(s), the examining attorney must refuse registration under Trademark Act §§1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1053, and 1127, because, absent a relevant prior registration, the gTLD would not be perceived by consumers as a mark.

In addition to the prior registration(s), the applicant must also submit a significant amount of additional evidence relevant to the issue of whether the mark, with or without the "." or "dot," will immediately function to identify the source of the domain registry operator and domain name registrar services rather than merely being perceived as a portion of an Internet domain name that can be acquired through applicant’s services. Because consumers are so highly conditioned, and may be predisposed, to view gTLDs as non-source-indicating, the applicant must show that consumers already will be so familiar with the wording as a mark that they will transfer the source recognition even to the domain registry operator and domain name registrar services. The amount of additional evidence required may vary, depending on the nature of the wording set out in the gTLD, Relevant evidence may include, but is not limited to: examples of advertising and promotional materials that specifically promote the mark shown in the application, with or without the "." or "dot," as a trademark or service mark in the United States; dollar figures for advertising devoted to such promotion; and/or sworn consumer statements of recognition of the applied-for mark as a trademark or service mark.

If the applicant has not entered into a Registry Agreement with ICANN designating the applicant as the Registry Operator for the gTLD identified by the mark, consumers may be deceived by use of a particular gTLD as a mark. Consumers generally would believe that the applicant’s domain registry operator and domain name registrar services feature the gTLD in the proposed mark, and would consider that material in the purchase of these services. Therefore, to avoid a deceptiveness refusal under §2(a) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(a); TMEP §§1203, 1203.02–1203.02(g), the applicant must: (1) submit evidence that it has entered into a currently valid Registry Agreement with ICANN, designating the applicant as the Registry Operator for the gTLD identified by the mark prior to registration and (2) indicate in the identification of services that the domain registry operator and domain name registrar services feature the gTLD shown in the mark.

If the application does not include a verified statement indicating that the applicant has an active or currently pending application for a Registry Agreement with ICANN designating the applicant as the Registry Operator for the gTLD identified by the mark, the examining attorney must issue an Office action with an information request under Trademark Rule 2.61(b), 37 C.F.R. 2.61(b), that requires the applicant to submit a verified statement indicating: (1) whether the applicant has in place, or has applied for, such a Registry Agreement with ICANN and (2) if the applicant has so applied, the current status of such application. The examining attorney must include an advisory indicating that if the applicant does not have a currently active, or currently pending application for a, Registry Agreement with ICANN designating the applicant as the Registry Operator for the gTLD identified by the mark, a deceptiveness refusal will be issued pursuant to §2(a). A currently pending application with ICANN avoids an immediate deceptiveness refusal, but as discussed below, the USPTO will not approve the trademark application for publication without proof of the award of the Registry Agreement.

If the applicant fails to respond to the information requirement, the examining attorney must maintain and continue the information requirement and issue a deceptiveness refusal under §2(a). If, in response to the information requirement, the applicant indicates that: (1) the applicant has not applied for a Registry Agreement with ICANN designating the applicant as the Registry Operator for the gTLD identified by the mark; (2) the applicant has applied for a Registry Agreement with ICANN designating the applicant as the Registry Operator for the gTLD identified by the mark, but that the application has not been approved and is no longer pending with ICANN; or (3) the applicant’s previous Registry Agreement with ICANN is no longer valid, the examining attorney must issue a deceptiveness refusal under §2(a).

If the applicant indicates that it has a currently pending application before ICANN for a Registry Agreement for the gTLD identified by the mark and the applicant has otherwise demonstrated that the mark consisting of the gTLD in the application before the USPTO could function as a mark, the examining attorney may suspend the application until the resolution of the applicant’s pending application with ICANN. See TMEP §716.02(i).

To be considered a service within the parameters of the Trademark Act, an activity must, inter alia, be primarily for the benefit of someone other than the applicant. See In re Reichhold Chems., Inc., 167 USPQ 376, 377 (TTAB 1970) ; TMEP §1301.01(a)(ii). Therefore, the examining attorney must issue an information request pursuant to Trademark Rule 2.61(b), 37 C.F.R. 2.61(b), to ascertain the following information to determine if the domain registry operator and domain name registrar services will be primarily for the benefit of others:

While operating a gTLD registry that is only available for the applicant’s employees or for the applicant’s marketing initiatives alone generally would not qualify as a service, registration for use by the applicant’s affiliated distributors typically would.

If the applicant fails to indicate for the record that the applicant’s domain registry operator and domain name registrar services are, or will be, primarily for the benefit of others, the examining attorney must refuse registration pursuant to §§1, 2, 3, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C §§1051-1053, 1127. See TMEP §1301.01(a)(ii).

The USPTO’s Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual (ID Manual) includes "domain registry operator services" in International Class 42 and "domain name registrar services" in International Class 45 for use by those entities with valid Registry Agreements or current accreditation as a registrar by ICANN.

A refusal of registration on the ground that the matter presented for registration does not function as a mark relates to the manner in which the asserted mark is used. Generally, in an intent-to-use application filed under §1(b) of the Trademark Act, a mark that includes a domain name will not be refused on this ground until the applicant has submitted specimen(s) of use and an allegation of use (i.e., either an amendment to allege use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(c) or a statement of use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(d) ). The specimen provides a better record upon which to determine the registrability of the mark. However, the examining attorney should include an advisory note in the first Office action that registration may be refused if the proposed mark, as used on the specimen, identifies only an Internet address. This is done strictly as a courtesy. If information regarding this possible ground for refusal is not provided to the applicant prior to the filing of the allegation of use, the USPTO is not precluded from refusing registration on this basis.

If the record indicates that the proposed mark would be perceived as merely an informational indication of the domain name address used to access a website rather than an indicator of source, the examining attorney must refuse registration in an application under §44 or §66(a) of the Trademark Act, on the ground that the subject matter does not function as a mark. The statutory bases for the refusals are §§1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, and 1127, for trademarks; and §§1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1053, and 1127, for service marks.

If a mark is composed of a surname and a non-source-identifying gTLD, the examining attorney must refuse registration because the mark is primarily merely a surname under Trademark Act §2(e)(4), 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(4), absent a showing of acquired distinctiveness under Trademark Act §2(f), 15 U.S.C. §1052(f). If the gTLD has no trademark significance, and the primary significance of a term is that of a surname, adding the gTLD to the surname does not alter the primary significance of the mark as a surname. Cf. In re I. Lewis Cigar Mfg. Co., 205 F.2d 204, 98 USPQ 265 (C.C.P.A. 1953) (S. SEIDENBERG & CO’S. for cigars held primarily merely a surname); In re Hamilton Pharms. Ltd., 27 USPQ2d 1939 (TTAB 1993) (HAMILTON PHARMACEUTICALS for pharmaceutical products held primarily merely a surname); In re Cazes, 21 USPQ2d 1796 (TTAB 1991) (BRASSERIE LIPP for restaurant services held primarily merely a surname where "brasserie" is a generic term for applicant’s restaurant services). See also TMEP §1211.01(b)(vi) regarding surnames combined with additional wording.

If a proposed mark is composed of a merely descriptive term(s) combined with a non-source-identifying gTLD, in general, the examining attorney must refuse registration under Trademark Act §2(e)(1), 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(1), on the ground that the mark is merely descriptive. This applies to trademarks, service marks, collective marks, and certification marks.

The gTLD will be perceived as part of an Internet address, and typically does not add source-identifying significance to the composite mark. In re 1800Mattress.com IP LLC, 586 F.3d 1359, 92 USPQ2d 1682 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (MATTRESS.COM generic for "online retail store services in the field of mattresses, beds, and bedding"); In re Hotels.com, L.P., 573 F.3d 1300, 91 USPQ2d 1532 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (HOTELS.COM generic for "providing information for others about temporary lodging; travel agency services, namely, making reservations and bookings for temporary lodging for others by means of telephone and the global computer network"); In re Reed Elsevier Props. Inc., 482 F.3d 1376, 82 USPQ2d 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (LAWYERS.COM generic for "providing access to an online interactive database featuring information exchange in the fields of law, lawyers, legal news, and legal services"); In re Oppedahl & Larson LLP, 373 F.3d 1171, 71 USPQ2d 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (PATENTS.COM merely descriptive of "computer software for managing a database of records and for tracking the status of the records by means of the Internet"); In re DNI Holdings Ltd., 77 USPQ2d 1435 (TTAB 2005) (SPORTSBETTING.COM generic for "provision of casino games on and through a global computer network wherein there are no actual monetary wagers; provision of contests and sweepstakes on and through a global computer network; providing a web site on and through a global computer network featuring information in the fields of gaming, athletic competition and entertainment"); In re Eddie Z’s Blinds and Drapery, Inc., 74 USPQ2d 1037 (TTAB 2005) (BLINDSANDDRAPERY.COM generic for retail store services featuring blinds, draperies, and other wall coverings, sold via the Internet); In re Microsoft Corp., 68 USPQ2d 1195 (TTAB 2003) (OFFICE.NET merely descriptive of various computer software and hardware products); In re CyberFinancial.Net, Inc., 65 USPQ2d 1789 (TTAB 2002) (BONDS.COM generic for providing information regarding financial products and services and electronic commerce services rendered via the Internet); In re Martin Container, Inc., 65 USPQ2d 1058 (TTAB 2002) (CONTAINER.COM generic for "retail store services and retail services offered via telephone featuring metal shipping containers" and "rental of metal shipping containers").

However, there is no bright-line, per se rule that the addition of a non-source-identifying gTLD to an otherwise descriptive mark will never under any circumstances operate to create a registrable mark. The Federal Circuit has cautioned that in rare, exceptional circumstances, a term that is not distinctive by itself may acquire some additional meaning from the addition of a gTLD such as ".com" or ".net." In re Steelbuilding.com, 415 F.3d 1293, 1297, 75 USPQ2d 1420, 1422 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (STEELBUILDING.COM highly descriptive, but not generic, for "computerized on-line retail services in the field of pre-engineered metal buildings and roofing systems," noting that "the addition of the TLD can show Internet-related distinctiveness, intimating some ‘Internet feature’ of the item.") (citing Oppedahl & Larson, 373 F.3d at 1175-1176, 71 USPQ2d at 1373).

Thus, when examining domain name marks, it is important to evaluate the commercial impression of the mark as a whole to determine whether the composite mark conveys any distinctive source-identifying impression apart from its individual components. The examining attorney must introduce evidence as to the significance of the individual components, including the gTLD, but must also consider the significance of the composite term (e.g., "Sportsbetting" in the mark SPORTSBETTING.COM) to determine whether the addition of the TLD has resulted in a mark that conveys a source-identifying impression.

See also TMEP §§1209.03(m), 1215.02(d)─1215.02(d)(iv), and 1215.05.

There is no per se rule that the addition of a generic term to a generic top-level domain (gTLD) (i.e., a "generic.com" term) can never under any circumstances operate to create a registrable mark. USPTO v. Booking.com B.V., 140 S. Ct. 2298, 2020 USPQ2d 10729 (2020) (holding that "[w]hether any given ‘generic.com’ term is generic ... depends on whether consumers in fact perceive that term as the name of a class or, instead, as a term capable of distinguishing among members of the class"). In reaching its decision in Booking.com, the Supreme Court left undisturbed a lower-court finding that ".com does not itself have source-identifying significance when added to a [second-level domain] like booking." Booking.com B.V. v. USPTO, 915 F.3d 171, 185 (4th Cir. 2019), aff’d, 140 S. Ct. 2298, 2301, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *2 (2020). Therefore, under Booking.com, a proposed mark composed of a generic term combined with a generic top-level domain, such as ".com," is not automatically generic, nor is it automatically non-generic. See Booking.com, 140 S. Ct. at 2307, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *7. Instead, as in any other genericness analysis, examining attorneys must evaluate all of the available evidence, including the applicant’s evidence of consumer perception, to determine whether the relevant consumers perceive the term as generic for the identified class of goods and/or services or, instead, as capable of serving as a mark. See id.; In re Consumer Prot. Firm PLLC, 2021 USPQ2d 238, at *6-9 (TTAB 2021).

Accordingly, generic.com terms are potentially capable of serving as a mark and may be eligible for registration on the Supplemental Register, or on the Principal Register upon a sufficient showing of acquired distinctiveness. However, a generic.com term may still be refused as generic when warranted by the evidence in the application record.

Although the Court in Booking.com rejected a per se rule that generic.com terms are automatically generic, it specifically declined to adopt a rule that these terms are automatically non-generic. See USPTO v. Booking.com B.V., 140 S. Ct. 2298, 2307, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *7 (2020). Thus, the decision did not otherwise significantly alter the genericness analysis to be applied to generic.com terms or the USPTO’s examination procedures regarding marks consisting of a generic.com term, that is, any combination of a generic term and generic top-level domain designating an entity or information, such as ".com," ".net," ".org," ".biz," or ".info." Thus, examining attorneys must continue to assess on a case-by-case basis whether, based on the evidence of record, consumers would perceive a generic.com term as the name of a class of goods and/or services or, instead, as at least capable of serving as a source indicator.

To establish that a generic.com term is generic and incapable of serving as a source indicator, the examining attorney must show that the relevant consumers would understand the primary significance of the term, as a whole, to be the name of the class or category of the goods and/or services identified in the application. See id. at 2304, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *5; In re 1800Mattress.com IP, LLC, 586 F.3d 1359, 1364, 92 USPQ2d 1682, 1685 (Fed.Cir. 2009) ("[I]t is irrelevant whether the relevant public refers to online mattress retailers as ‘mattress.com.’. . . the correct inquiry is whether the relevant public would understand, when hearing the term ‘mattress.com,’ that it refers to online mattress stores"); H. Marvin Ginn Corp. v. Int’l Ass’n of Fire Chiefs, Inc., 782 F.2d 987, 989-90, 228 USPQ 528, 530 (Fed. Cir. 1986); TMEP §1209.01(c)(i). Generally, evidence showing generic use of the generic.com term in its entirety, including evidence of domain names containing the term for third-party websites offering the same types of goods or services, is a competent source of the consumers’ understanding that will support a finding of genericness. See Princeton Vanguard, LLC v. Frito-Lay N. Am., Inc., 786 F.3d 960, 968, 114 USPQ2d 1827, 1832 (Fed. Cir. 2015); TMEP §1209.01(c)(i); see also In re Hotels.com, L.P., 573 F.3d 1300, 1304, 91 USPQ2d 1532, 1535-36 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (evidence of similar usages of "hotels.com" in domain names of others providing hotel information and reservation services supported a prima facie case of genericness); In re Reed Elsevier Props., 482 F.3d 1376, 1379-80, 82 USPQ2d 1378, 1380-81 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (evidence of eight websites containing "lawyer.com" or "lawyers.com" in the domain name constituted substantial evidence to support the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board’s (TTAB) finding that "LAWYERS.COM" is generic for the service of providing an online interactive database featuring information exchange in the field of law, legal news, and legal services). However, even in the absence of such evidence, a genericness refusal may be appropriate if the evidence of record otherwise establishes that the combination of the generic elements of the proposed mark "yields no additional meaning to consumers capable of distinguishing the goods or services." See Booking.com, 140 S. Ct. at 2306, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *7; see also TMEP §1209.01(c)(i).

Evidence of consumer perception may include "dictionaries, usage by consumers and competitors, use in the trade, and any other source of evidence bearing on how consumers perceive a term’s meaning," including relevant and probative consumer surveys. Booking.com, 140 S. Ct. at 2307 n.6, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *7 n.6. These are the same types of evidence examining attorneys traditionally consider when assessing genericness. See, e.g., In re Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner, & Smith, Inc., 828 F.2d 1567, 1570, 4 USPQ2d 1141, 1143 (Fed. Cir. 1987) ("Evidence of the public’s understanding of the term may be obtained from any competent source, such as purchaser testimony, consumer surveys, listings in dictionaries, trade journals, newspapers, and other publications.").

The following are examples of the types of evidence that may support the conclusion that consumers would perceive the generic.com term, as a whole, as the name of the class of goods and/or services:

See In re Hotels.com, L.P., 573 F.3d 1300, 91 USPQ2d 1532 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (affirming the TTAB’s finding that HOTELS.COM is generic for "providing information for others about temporary lodging; [and] travel agency services, namely, making reservations and bookings for temporary lodging for others by means of telephone and the global computer network," based on various definitions of "hotel," printouts from hotel reservation search websites showing "hotels" as the equivalent of or included within "temporary lodging," and evidence from the applicant’s website); TMEP §1209.01(c)(i).

When issuing a genericness refusal, the examining attorney must explain how the evidence of record supports the conclusion not only that the individual elements of the generic.com term are generic, but also that, when combined, the combination creates no new or additional significance among consumers capable of indicating source. See In re 1800Mattress.com IP, 586 F.3d 1359, 1363, 92 USPQ2d 1682, 1684 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (affirming the TTAB’s conclusion that MATTRESS.COM is generic for "online retail store services in the field of mattresses, beds, and bedding," where the TTAB considered each of the constituent words, "mattress" and ".com," and determined that they were both generic, and then considered the mark as a whole and determined that the combination added no new meaning, relying on the prevalence of the term "mattress.com" in the website addresses of several online mattress retailers who provide the same services as the applicant); In re Hotels.com, L.P., 573 F.3d at 1306, 91 USPQ2d at 1537; TMEP §1209.01(c)(i).

Consistent with existing examination procedures, the examining attorney must not initially refuse registration of a generic.com term on the Principal Register as generic, even if there is strong evidence of genericness. See TMEP §1209.02(a). Instead, the examining attorney must refuse the proposed mark as merely descriptive under Trademark Act Section 2(e)(1), 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(1), and provide relevant supporting evidence. See id. If the evidence strongly suggests that the generic.com term is not capable of serving as a source indicator, the refusal must include an advisory that a claim of acquired distinctiveness or an amendment to the Supplemental Register is not recommended. See id. If, on the other hand, the examining attorney determines that the generic.com term is at least capable of serving as a source indicator based on the available evidence, then the examining attorney may advise that the applicant may amend the application to the Supplemental Register. See TMEP §816.04. If the record creates doubt as to whether the applied-for generic.com term is capable of functioning as a mark, the examining attorney must refrain from giving any advisory statement. See TMEP §1209.02(a).

If the initial application seeks registration on the Supplemental Register or on the Principal Register under a claim of acquired distinctiveness, and there is strong evidence of genericness, then a refusal on the basis that the generic.com term is generic will be appropriate.

If the application itself or a subsequent submission includes a claim of acquired distinctiveness under Trademark Act Section 2(f), 15 U.S.C. §1052(f), the examining attorney must carefully review the applicant’s evidence in support of the claim, along with all other available evidence, to determine whether the relevant consumers have, in fact, come to view the proposed generic.com term as an indicator of source for the identified goods and/or services. See generally TMEP §§1212.01-1212.02.

Under Booking.com, generic.com terms are neither per se generic, nor per se non-generic. See USPTO v. Booking.com B.V., 140 S. Ct. 2298, 2307, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *7 (2020). However, given the nature of these terms, the available evidence will likely support a conclusion that they are, at least, highly descriptive, and thus consumers would be less likely to believe that they indicate source in any party. See In re Steelbuilding.com, 415 F.3d 1293, 1301, 75 USPQ2d 1420, 1424 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (holding that STEELBULDING.COM was highly descriptive and unregistrable on the Principal Register under §2(e)(1), absent "a concomitantly high level of secondary meaning."). Thus, for generic.com terms, applicants will generally have a greater evidentiary burden to establish that the proposed mark has acquired distinctiveness. See Royal Crown Co. v. Coca-Cola Co., 892 F.3d 1358, 1368, 127 USPQ2d 1041, 1047 (Fed. Cir. 2018); In re Nat’l Ass’n of Veterinary Technicians in Am., 2019 USPQ2d 269108, at *6 (TTAB 2019); In re Yarnell Ice Cream, LLC, 2019 USPQ2d 265039, at *9 (TTAB 2019); see also TMEP §1212.01.

Accordingly, evidence of five years’ use or reliance solely on a prior registration for the same term will usually be insufficient to support a Section 2(f) claim for a generic.com term. See TMEP §§1212.04-1212.04(a), 1212.05(a). Typically, the applicant will need to provide a significant amount of actual evidence that the generic.com term has acquired distinctiveness in the minds of consumers. See TMEP §§1212.06-1212.06(e)(vi).

Evidence submitted in support of the Section 2(f) claim may include consumer surveys; consumer declarations; declarations or other relevant and probative evidence showing the duration, extent, and nature of the applicant’s use of the proposed mark, including the degree of exclusivity of use; related advertising expenditures; letters or statements from the trade or public; and any other appropriate evidence tending to show that the proposed mark distinguishes the goods or services to consumers. See 37 C.F.R. §2.41; TMEP §§1212.06-1212.06(e)(vi).

Regarding consumer surveys, in particular, the Supreme Court cautioned that they must be properly designed and interpreted to ensure that they are an accurate and reliable representation of consumer perception of a proposed mark. See Booking.com, 140 S. Ct. at 2307 n.6, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *7 n.6.; accord id. at 2309, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *9 (Sotomayor, J., concurring) ("Flaws in a specific survey design, or weaknesses inherent in consumer surveys generally, may limit the probative value of surveys in determining whether a particular mark is descriptive or generic in this context."). Therefore, an applicant submitting a survey must carefully frame its questions and provide a report, typically from a survey expert, documenting the procedural aspects of the survey and statistical accuracy of the results. See TMEP §1212.06(d). Information regarding how the survey was conducted, the questionnaire itself, the universe of consumers surveyed, the number of participants surveyed, and the geographic scope of the survey should be submitted within or along with such a report. See id. If this information is not provided, the examining attorney may request it under 37 C.F.R. §2.61(b).

If the examining attorney determines that the evidence of record establishes that the generic.com term is, in fact, a generic name for the identified goods and/or services, the examining attorney must refuse registration on the ground that the term is generic and indicate that the claim of acquired distinctiveness does not overcome the refusal. See TMEP §§1209.02(a)(ii), 1209.02(b). The statutory basis for this refusal is Trademark Act Sections 1, 2, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, and 1127, for goods, or Sections 1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1053, and 1127, for services. In addition to this refusal, the examining attorney must issue or maintain, in the alternative, a refusal under Trademark Act Section 2(e)(1) on the ground that the proposed mark is merely descriptive. See Id. This refusal must separately explain why the showing of acquired distinctiveness is insufficient to overcome the descriptiveness refusal even if the proposed mark is ultimately deemed not to be generic. See Id.

If the application itself or a subsequent submission requests registration on the Supplemental Register, and the evidence supports a determination that the proposed generic.com term is generic, registration must be refused under Trademark Act Sections 23(c) and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1091(c), 1127. See TMEP §1209.02(a)(i).

If the examining attorney determines that the available evidence establishes that the proposed generic.com term is at least capable of indicating source but is insufficient to show that the term has acquired distinctiveness, the examining attorney may allow registration on the Supplemental Register, if otherwise appropriate. See TMEP §§815-815.02.

Examining attorneys must follow existing disclaimer policy and procedure when examining proposed marks containing generic.com terms and other matter. See generally TMEP §§1213-1213.11. If the examining attorney determines that, based on the evidence, the generic.com term is incapable of serving as a source indicator and is separable from the other matter in the proposed mark, a disclaimer of the term is appropriate, whether registration is sought on the Principal Register or Supplemental Register. See TMEP §1213.03(b). Generally, when disclaiming a generic.com term, the term must be disclaimed in its entirety, rather than disclaiming the generic term and the generic top-level domain separately. See TMEP §1213.08(b).

If an applicant claims acquired distinctiveness in part as to a generic.com term that is combined with other matter, the evidence of acquired distinctiveness should be evaluated in accordance with TMEP §1215.05(b)(i).

Examining attorneys must also consider whether the specimen of use shows the generic.com term being used solely as a website address and not in a trademark or service mark manner. If so, a refusal on the ground that the proposed mark fails to function as a trademark or service mark is appropriate. See TMEP §1202. The statutory basis for this refusal is Trademark Act Sections 1, 2, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, and 1127, for goods, or Sections 1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1053, and 1127, for services. The statutory basis for refusal of registration on the Supplemental Register of matter that does not function as a mark is Sections 23(c) and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1091(c), 1127.

In Booking.com, the Supreme Court recognized that registered generic.com terms may be subject to a narrower scope of trademark protection, noting that "[w]hen a mark incorporates generic or highly descriptive components, consumers are less likely to think that other uses of the common element emanate from the mark’s owner." USPTO v. Booking.com B.V., 140 S. Ct. 2298, 2307, 2020 USPQ2d 10729, at *7 (2020).

Accordingly, examining attorneys may take this into account when considering whether a prior registration for a generic.com term that contains the same generic or highly descriptive terms that appear in a proposed mark should be cited under Trademark Act Section 2(d). Generally, in these circumstances, if there is other matter in either of the marks that would allow consumers to differentiate them, the examining attorney may reasonably determine that confusion as to source is not likely. Cf. TMEP §1207.01(d)(iii) ("[A]ctive third-party registrations may be relevant to show that a mark or a portion of a mark is descriptive, suggestive, or so commonly used that the public will look to other elements to distinguish the source of the goods or services."). However, each case must be considered on its own merits, with consideration given to all relevant likelihood-of-confusion factors for which there is evidence of record. See TMEP §1207.01. For more information regarding Section 2(d) and domain names, see TMEP §1215.09.

The examining attorney should examine marks containing geographic matter along with a gTLD in the same manner that any mark containing geographic matter is examined. See generally TMEP §§1210–1210.10. Depending on the manner in which it is used on or in connection with the goods or services, a proposed domain name mark containing a geographic term may be primarily geographically descriptive under §2(e)(2) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(2), primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive under §2(e)(3) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(3), deceptive under §2(a) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(a), and/or merely descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive under §2(e)(1) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(1).

When a geographic term is used as a mark for services that are provided on the Internet, the geographic term sometimes describes the subject of the service rather than the geographic origin of the service. Usually this occurs when the mark is composed of a geographic term that describes the subject matter of information services (e.g., NEW ORLEANS.COM for "providing vacation planning information about New Orleans, Louisiana by means of the global computer network"). In these cases, the examining attorney must refuse registration under §2(e)(1) because the mark is merely descriptive of the services. See TMEP §1210.02(b)(iii).

Trademark Act §6(a), 15 U.S.C. §1056(a), provides for the disclaimer of "an unregistrable component of a mark otherwise registrable." The guidelines on disclaimer discussed in TMEP §§1213–1213.11 apply to domain name mark applications.

If a composite mark includes a domain name composed of unregistrable matter (e.g., a merely descriptive or generic term and a non-source-identifying gTLD), disclaimer is required.

If a disclaimer is required and the domain name includes a misspelled or telescoped word, the correct spelling must be disclaimed. See TMEP §§1213.05(a)(i) and 1213.08(c).

A compound term composed of arbitrary or suggestive matter combined with a "dot" and a non-source-identifying gTLD is considered unitary, and, therefore, no disclaimer of the gTLD is required. See examples below and TMEP §§1213.05–1213.05(g)(iv) regarding unitary marks.

| Mark | Disclaimer |

|---|---|

| ABC BANK.COM | BANK.COM |

| ABC FEDERALBANK.COM | FEDERAL BANK.COM |

| ABC GROCERI STOR.COM | GROCERY STORE.COM |

| ABC.COM | no disclaimer |

| ABC.BANK.COM | no disclaimer |

| ABCBANK.COM | no disclaimer |

Amendments may not be made to the drawing of the mark if the character of the mark is materially altered. 37 C.F.R. §2.72. In determining whether an amendment is a material alteration, the controlling question is always whether the new and old forms of the mark create essentially the same commercial impression. See TMEP §§807.14–807.14(f) regarding further information about material alteration. In re Yale Sportswear Corp., 88 USPQ2d 1121 (TTAB 2008) ( mark on the specimen (UPPER 90°) not a substantially exact representation of the mark on the drawing (UPPER 90); In re Innovative Cos., LLC, 88 USPQ2d 1095 (TTAB 2008) ( proposed amendment of the drawing from FREEDOMSTONE to FREEDOM STONE not material alteration of the mark); Paris Glove of Can., LTD, v. SBC/Sporto Corp., 84 USPQ2d 1856, 1862 (TTAB 2007) (in an application to renew a registration, the old and new specimens (AQUA STOP and AQUASTOP, both stylized) were deemed to be substantially the same because "mere changes in background or styling, or modernization, are not ordinarily considered to be material changes in the mark.").

Generally, an applicant may add or delete a non-source-identifying gTLD to/from the drawing of a domain name mark (e.g., COOPER amended to COOPER.COM, or COOPER.COM amended to COOPER) that includes an inherently distinctive or descriptive second-level domain name without materially altering the mark. Although a mark that includes a gTLD generally will be perceived by the public as a domain name, while a mark without a gTLD will not, if the gTLD merely indicates the type of entity using the domain name, the essence of the mark in such cases is created by the second-level domain name, not the gTLD. Thus, the commercial impression created by the second-level domain name usually remains the same whether the non-source-identifying gTLD is present or not. If the gTLD does function as a source indicator, its deletion from the domain name mark may constitute a material alteration of the mark.

Example: Amending a mark from PETER to PETER.COM would not materially change the mark because the essence of both marks is still PETER, a person’s name.

Example: Amending a mark from ABC.PETER to ABC would materially change the mark because the essence of the original mark is created by both the second-level domain and the gTLD.

Similarly, substituting one non-source-identifying gTLD for another in a domain name mark, or adding or deleting a "dot" or "http://www." or "www." to a domain name mark is generally permitted.

Example: Amending a mark from ABC.ORG to ABC.COM would not materially change the mark because the essence of both marks is still ABC.

Example: Amending a mark from ABC.COM to ABC.PETER would materially change the mark because the essence of the original mark was ABC and the proposed mark now includes a source-identifying gTLD.

If a mark that is not used as an Internet domain name includes a gTLD, adding or deleting the gTLD may be a material alteration.

Example: Deleting the term .COM from the mark ".COM ☼" used on printed sports magazines would materially change the mark.

When used in connection with domain registry operator or domain name registrar services, wording immediately preceded by a dot (".") will likely be viewed by consumers as a gTLD. On the other hand, the same wording, used in connection with the same services, but shown without the "." would not give the impression of a gTLD and could be viewed as an indicator of source, such that the commercial impression created by the marks materially differs. Thus, the "." in this context does not constitute the type of "extraneous, nondistinctive punctuation" discussed in TMEP §807.12(a)(i).

Accordingly, an applicant may not amend an application to add a "." before wording in a mark for which the identification of services encompasses domain name registry operator or registrar services. Nor may an applicant amend a drawing to delete a "." from the beginning of wording in a mark in these instances.

Example: Amending an applied-for mark from TMARKIE to .TMARKIE would materially change the commercial impression of the mark from that of a source-indicating mark to that of a gTLD.

When analyzing whether a domain name mark is likely to cause confusion with another pending or registered mark, the examining attorney must consider the marks as a whole, but generally should accord little weight to a non-source-identifying gTLD portion of the mark. Apple Comput. v. TVNET.net, Inc., 90 USPQ2d 1393 (TTAB 2007); see TMEP §1207.01(b)(iii). For more information regarding Section 2(d) and generic.com terms, see TMEP §1215.05(e).

Marks that contain the phonetic equivalent of a non-source-identifying gTLD (e.g., ABC DOTCOM) are treated in the same manner as marks composed of the gTLD itself. If a disclaimer is necessary, the disclaimer must be in the form of the gTLD and not the phonetic equivalent. See TMEP §1213.08(c) regarding disclaimer of misspelled words.

Example: The mark is INEXPENSIVE RESTAURANTS DOT COM for providing information about restaurants by means of a global computer network. Registration must be refused because the mark is merely descriptive of the services under 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(1).

Example: The mark is ABC DOTCOM. The applicant must disclaim the gTLD ".COM" rather than the phonetic equivalent "DOTCOM."

Trademark rights are not static, and eligibility for registration must be determined on the basis of the facts and evidence of record that exist at the time registration is sought. In re Morton-Norwich Prods., Inc., 671 F.2d 1332, 213 USPQ 9 (C.C.P.A. 1982) ; In re Thunderbird Prods. Corp., 406 F.2d 1389, 160 USPQ 730 (C.C.P.A. 1969) ; In re Sun Microsystems Inc., 59 USPQ2d 1084 (TTAB 2001) ; In re Styleclick.com Inc., 58 USPQ2d 1523 (TTAB 2001) ; In re Styleclick.com Inc., 57 USPQ2d 1445 (TTAB 2000) .

Each case must be decided on its own facts. The USPTO is not bound by the decisions of the examiners who examined the applications for the applicant’s previously registered marks, based on different records. See In re Cordua Rests., Inc., 823 F.3d 594, 600, 118 USPQ2d 1632, 1635 (Fed. Cir. 2016) ("The PTO is required to examine all trademark applications for compliance with each and every eligibility requirement . . . even if the PTO earlier mistakenly registered a similar or identical mark suffering the same defect."); In re Omega SA, 494 F.3d 1362, 83 USPQ2d 1541 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (upholding examining attorney’s requirement for amendment of the term "chronographs" in the identification of goods, notwithstanding applicant’s ownership of several registrations in which this term appears without further qualification in the identification); In re Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner, & Smith Inc., 828 F.2d 1567, 4 USPQ2d 1141 (Fed. Cir. 1987) (incontestable registration of CASH MANAGEMENT ACCOUNT for credit card services did not automatically entitle applicant to registration of the same mark for broader financial services); In re Loew’s Theatres, Inc., 769 F.2d 764, 226 USPQ 865 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (examining attorney could properly refuse registration on ground that DURANGO for chewing tobacco is primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive, even though applicant owned incontestable registration of same mark for cigars); In re Am. Furniture Warehouse CO, 126 USPQ2d 1400, 1407 (TTAB 2018) ("[C]onsistency in examination is not itself a substantive rule of trademark law, and a desire for consistency with the decisions of prior examining attorneys must yield to proper determinations under the Trademark Act and rules."); In re USA Warriors Ice Hockey Program, Inc., 122 USPQ2d 1790, 1793 n.10 (TTAB 2017) ("The issuance of Applicant's first registration does not require the approval of a second registration if, on the facts of the case, it would be improper to do so under the governing legal standard."); In re Rodale Inc., 80 USPQ2d 1696 (TTAB 2006) (NUTRITION BULLETIN generic for "providing information in the field of health and diet via a web site on the Internet," notwithstanding applicant’s claims of ownership of six prior registrations on the Supplemental Register that included the term "bulletin" in the mark for related goods and services (e.g., "Weight-Loss Bulletin," "Sex Bulletin," "Muscle Bulletin," and "Nutrition Bulletin")); In re Best Software Inc., 58 USPQ2d 1314 (TTAB 2001) (applicant’s ownership of registration of BEST! did not preclude examining attorney from requiring disclaimer of "Best" in applications seeking registration of BEST! SUPPORTPLUS and BEST! SUPPORTPLUS PREMIER for the same and additional services); In re Sunmarks Inc., 32 USPQ2d 1470 (TTAB 1994) (examining attorney not precluded from refusing registration of ULTRA for "gasoline, motor oil, automotive grease, general purpose grease, machine grease and gear oil," even though applicant owned registrations of same mark for "motor oil" and "gasoline for use as automotive fuel, sold only in applicant’s automotive service stations"); In re Medical Disposables Co., 25 USPQ2d 1801 (TTAB 1992) (disclaimer of the unitary term "MEDICAL DISPOSABLES" required, notwithstanding applicant’s ownership of a prior registration in which a piecemeal disclaimer of the words "MEDICAL" and "DISPOSABLES" was permitted); In re Perez, 21 USPQ2d 1075 (TTAB 1991) (likelihood of confusion between applicant’s EL GALLO for fresh tomatoes and peppers and the previously registered mark ROOSTER for fresh citrus fruit, notwithstanding applicant’s ownership of an expired registration of the same mark for the same goods); In re Lean Line, Inc., 229 USPQ 781 (TTAB 1986) (LEAN merely descriptive of low-calorie foods, even though applicant had registered the term for other goods and services and a third-party had registered the term "LEAN CUISINE" with no disclaimer); In re McDonald’s Corp., 229 USPQ 555 (TTAB 1985) (Board not bound to allow registration of APPLE PIE TREE for restaurant services merely because applicant had succeeded in registering the character and name as trademarks and the character as a service mark); In re Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 222 USPQ 820 (TTAB 1984) (LAW & BUSINESS incapable of distinguishing the services of arranging and conducting seminars in the field of business law, notwithstanding applicant’s ownership of a registration on the Supplemental Register for the same mark for books, pamphlets, and monographs); In re Local Trademarks, Inc., 220 USPQ 728 (TTAB 1983) (upholding refusal of registration on the ground that WHEN IT’S TIME TO ACT did not identify advertising services; Board not bound to allow registration simply because applicant owned registrations for identical services); In re Pilon, 195 USPQ 178 (TTAB 1977) (title of chapter or section of book not registrable, even though applicant owned prior registrations of marks comprising chapter titles). See also In re Wilson, 57 USPQ2d 1863 (TTAB 2001) ("reasoned decisionmaking" doctrine, which prohibits a federal agency from creating conflicting lines of precedent governing identical situations, did not entitle applicant to registration of PINE CONE BRAND for packaged fresh citrus fruit, even though USPTO issued registration for similar PINE CONE mark in 1933 despite then-existing registration for PINE CONE mark that was cited against applicant).

Section 15 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1065, provides a procedure by which a registrant’s exclusive right to use a mark in commerce on or in connection with the goods or services covered by the registration can become incontestable. See TMEP §§1605–1605.06 for information about the requirements for filing an affidavit of incontestability under §15.

In Park ‘N Fly v. Dollar Park & Fly, Inc., 469 U.S. 189, 224 USPQ 327 (1985), the Supreme Court held that the owner of a registered mark may rely on incontestability to enjoin infringement, and that an incontestable registration, therefore, cannot be challenged on the ground that the mark is merely descriptive.

In In re Am. Sail Training Ass’n, 230 USPQ 879 (TTAB 1986), the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board held that an examining attorney could not require a disclaimer of "TALL SHIPS" in an application for registration of the mark RETURN OF THE TALL SHIPS, where the applicant owned an incontestable registration for the mark TALL SHIPS for the identical services. This would be a collateral attack on an incontestable registration. However, this applies only where both the marks and the goods or services are identical, and the identical part of the applied-for mark would not be considered generic. The Board noted that the matter required to be disclaimed was "identical to the subject matter of applicant’s incontestable registration," and that "the services described in applicant’s application are identical to those recited in the prior incontestable registration." Id. at 880.

For determining likelihood of confusion, "the fact that opposer's federally registered trademark has achieved incontestable status means that it is conclusively considered to be valid, but it does not dictate that the mark is 'strong.'" Safer, Inc. v. OMS Invs., Inc., 94 USPQ2d 1031, 1036 (TTAB 2010). Moreover, although "an incontestable registration may not be challenged as invalid for mere descriptiveness," incontestability does not preclude a finding that, in terms of conceptual strength, the mark is descriptive for purposes of determining the inherent strength of a mark as a factor relevant to likelihood of confusion. Couch/Braunsdorf Affinity, Inc. v. 12 Interactive, LLC, 110 USPQ2d 1458, 1476-77 (TTAB 2014); see also In re Fat Boys Water Sports LLC, 118 USPQ2d 1511, 1517-18 (TTAB 2016) (noting that registrant’s mark was "presumptively distinctive" under Trademark Act §§7(b) and 33(a), but finding that the evidence showed that the mark was "nevertheless weak as a source indicator" for purposes of determining likelihood of confusion).

Ownership of an incontestable registration does not give the applicant a right to register the same mark for different goods or services, even if they are closely related to the goods or services in the incontestable registration. See In re Save Venice N.Y. Inc., 259 F.3d 1346, 1353, 59 USPQ2d 1778, 1782 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (applicant’s ownership of incontestable registration of the word mark SAVE VENICE for newsletters, brochures, and fundraising services did not preclude examining attorney from refusing registration of a composite mark consisting of the phrases THE VENICE COLLECTION and SAVE VENICE INC. with an image of the winged Lion of St. Mark for different goods; "[a] registered mark is incontestable only in the form registered and for the goods or services claimed."); In re Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner, & Smith Inc., 828 F.2d 1567, 4 USPQ2d 1141 (Fed. Cir. 1987) (incontestable registration of CASH MANAGEMENT ACCOUNT for credit card services did not automatically entitle applicant to registration of the same mark for broader financial services); In re Bose Corp., 772 F.2d 866, 873, 227 USPQ 1, 6–7 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (incontestable status of registration for one speaker design did not establish nonfunctionality of another speaker design with shared feature); In re Loew’s Theatres, Inc., 769 F.2d 764, 226 USPQ 865 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (examining attorney could properly refuse registration on ground that mark DURANGO for chewing tobacco is primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive, even though applicant owned incontestable registration of same mark for cigars); In re Best Software Inc., 63 USPQ2d 1109, 1113 (TTAB 2002) (applicant’s ownership of incontestable registration for the mark BEST! did not preclude examining attorney from requiring disclaimer of "BEST" in applications seeking registration of BEST! IMPERATIV HRMS "for goods which, although similar, are nevertheless somewhat different"); In re Best Software Inc., 58 USPQ2d 1314 (TTAB 2001) (applicant’s ownership of incontestable registration for the mark BEST! did not preclude the examining attorney from requiring disclaimer of "BEST" in applications seeking registration of BEST! SUPPORTPLUS and BEST! SUPPORTPLUS PREMIER for the same and additional services); In re Industrie Pirelli Societa per Azioni, 9 USPQ2d 1564 (TTAB 1988) (examining attorney could properly refuse registration on the ground that a mark is primarily merely a surname even if applicant owned incontestable registration of same mark for unrelated goods); In re BankAmerica Corp., 231 USPQ 873 (TTAB 1986) (examining attorney could refuse registration of BANK OF AMERICA under §§2(e)(1) and 2(e)(2), despite applicant’s ownership of incontestable registrations of same mark for related services); see also In re Cordua Rests., Inc., 823 F.3d 594, 600, 118 USPQ2d 1632, 1635 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (finding that the Board did not err in declining to consider the alleged incontestability of a prior registered standard-character word mark in evaluating the genericness of the stylized form thereof in connection with the same services).

A prior adjudication against an applicant may be dispositive of a later application for registration of the same mark on the basis of the same facts and issues, under the doctrine of res judicata, collateral estoppel, or stare decisis. Prior adjudications include decisions of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board or any of the reviewing courts.

Res Judicata. Res judicata, or claim preclusion, protects against relitigation of a previously adjudicated claim between the same parties or their privies based on the same cause of action. In re Bose Corp., 476 F.3d 1331, 1335, 81 USPQ2d 1748, 1752 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (quoting Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322, 326 (1979)).