A claim of distinctiveness by the applicant under §2(f) is usually made either in response to a statutory refusal to register or in anticipation of such a refusal. See TMEP §714.05(a)(i). A claim of distinctiveness is appropriately made in response to, or in anticipation of, only certain statutory refusals to register. For example, it is inappropriate to assert acquired distinctiveness to contravene a refusal under §2(a), (b), (c), (d), or (e)(5), 15 U.S.C. §1052(a), (b), (c), (d), (e)(5). Furthermore, acquired distinctiveness may not be asserted to contravene a refusal under §2(e)(3), 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(3), unless the mark became distinctive of the applicant’s goods in commerce before December 8, 1993, the date of enactment of the NAFTA Implementation Act (see TMEP §1210.07(b)). See TMEP §§1210.05(d)–1210.05(d)(ii) regarding procedures for refusing registration under §2(a) in response to a claim that a geographically deceptive mark acquired distinctiveness prior to December 8, 1993.

In In re Soccer Sport Supply Co., 507 F.2d 1400, 1403 n.3, 184 USPQ 345, 348 n.3 (C.C.P.A. 1975), the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals noted as follows:

[T]he judicially developed concept of "secondary meaning," codified by section 2(f) (15 U.S.C. 1052(f)), relates to descriptive, geographically descriptive, or surname marks which earlier had a primary meaning which did not indicate a single source and were, therefore, unregistrable because of section 2(e) (citation omitted). Additionally, section 2(f) has been applied to permit registration of a mark consisting solely of a design and, therefore, not within the purview of section 2(e).

For procedural purposes, a claim of distinctiveness under §2(f), whether made in the application as filed or in a subsequent amendment, may be construed as a concession that the matter to which it pertains is not inherently distinctive and, thus, not registrable on the Principal Register absent proof of acquired distinctiveness. See Cold War Museum, Inc. v. Cold War Air Museum, Inc., 586 F.3d 1352, 92 USPQ2d 1626, 1629 (Fed. Cir. 2009) ("Where an applicant seeks registration on the basis of Section 2(f), the mark's descriptiveness is a nonissue; an applicant’s reliance on Section 2(f) during prosecution presumes that the mark is descriptive."); In re Am. Furniture Warehouse CO, 126 USPQ2d 1400, 1403 (TTAB 2018) (noting that a claim of acquired distinctiveness by applicant to overcome a refusal in a prior registration for the same wording in connection with the same services "can be viewed as a concession by [a]pplicant that the wording itself is not inherently distinctive for those services"). For the purposes of establishing that the subject matter is not inherently distinctive, the examining attorney may rely on this concession alone. Once an applicant has claimed that matter has acquired distinctiveness under §2(f), the issue to be determined is not whether the matter is inherently distinctive but, rather, whether it has acquired distinctiveness. See, e.g., Yamaha Int’l Corp. v. Hoshino Gakki Co. , 840 F.2d 1572, 1577, 6 USPQ2d 1001, 1005 (Fed. Cir. 1988); In re Guaranteed Rate, Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 10869, at *2 (TTAB 2020); Spiritline Cruises LLC v. Tour Mgmt. Servs., Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 48324, at *5 (TTAB 2020); In re Hikari Sales USA, Inc., 2019 USPQ2d 111514, at *1 (TTAB 2019).

However, claiming distinctiveness in the alternative is not an admission that the proposed mark is not inherently distinctive. TMEP §1212.02(c).

See TMEP §1212.02(d) regarding unnecessary §2(f) claims.

An applicant may argue the merits of an examining attorney’s refusal and, in the alternative, claim that the matter sought to be registered has acquired distinctiveness under §2(f). Unlike the situation in which an applicant initially seeks registration under §2(f) or amends its application without objection, the alternative claim does not constitute a concession that the matter sought to be registered is not inherently distinctive. See In re Thomas Nelson, Inc., 97 USPQ2d 1712, 1713 (TTAB 2011) ; In re E S Robbins Corp., 30 USPQ2d 1540, 1542 (TTAB 1992); In re Prof'l Learning Ctrs., Inc., 230 USPQ 70, 71 n.2 (TTAB 1986) .

When an applicant claims acquired distinctiveness in the alternative, the examining attorney must treat separately the questions of: (1) the underlying basis of refusal; and (2) assuming the matter is determined to be registrable, whether acquired distinctiveness has been established. See, e.g., In re Olin Corp., 124 USPQ2d 1327, 1329 (TTAB 2107) ("It has long been established . . . that whether a mark is primarily merely a surname and whether it has acquired secondary meaning are separate considerations under the Trademark Act."). If the applicant has one or more prior registrations under §2(f) for a different depiction of the same mark (e.g., stylized vs. standard character) or a portion of the proposed mark, and for the same goods/services, the examining attorney’s review of the records of the registrations would reveal whether the applicant previously conceded descriptiveness or whether the Board found the mark descriptive on appeal. See In re Thomas Nelson, 97 USPQ2d at 1713. Such an assessment of the probative value of the prior registrations might also assist in resolving whether the mark in question has acquired distinctiveness, thereby obviating the necessity of determining that issue on appeal as well. Id.

In the event of an appeal on both grounds, the Board will use the same analysis, provided the evidence supporting the §2(f) claim is in the record and the alternative grounds have been considered and finally decided by the examining attorney. In re Harrington, 219 USPQ 854, 855 n.1 (TTAB 1983). If the appeal results in a finding of descriptiveness, and also that the mark has acquired distinctiveness, then descriptiveness would be present, even though not conceded by the applicant. In re Thomas Nelson, 97 USPQ2d at 1713.

If the examining attorney accepts the §2(f) evidence, the applicant must be given the option of publication under §2(f) or going forward with the appeal on the underlying refusal. This should be done by telephone or email, with a Note to the File in the record indicating the applicant’s decision, wherever possible. If the applicant wants to appeal, or if the examining attorney is unable to reach the applicant by telephone or email, the examining attorney must issue a written action continuing the underlying refusal and noting that the §2(f) evidence is deemed acceptable and will not be an issue on appeal.

Similarly, in an application under §1 or §44 of the Trademark Act, the applicant may seek registration on the Principal Register under §2(f) and, in the alternative, on the Supplemental Register. Depending on the facts of the case, this approach may have limited practical application. If the examining attorney finds that the matter sought to be registered is not a mark within the meaning of §§1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1127 (e.g., is generic or purely ornamental) (or §§1, 2, 4, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1054, 1127, for collective and certification marks), the examining attorney will refuse registration on both registers.

However, if the issues are framed in the alternative (i.e., whether the matter sought to be registered has acquired distinctiveness under §2(f) or, in the alternative, whether it is capable of registration on the Supplemental Register), and it is ultimately determined that the matter is a mark within the meaning of the Act (e.g., that the matter is merely descriptive rather than generic), then the evidence of secondary meaning will be considered. If it is determined that the applicant’s evidence is sufficient to establish that the mark has acquired distinctiveness, the application will be approved for publication on the Principal Register under §2(f). If the evidence is determined to be insufficient, the mark may be registered on the Supplemental Register in an application under §1 or §44 of the Trademark Act.

Accordingly, the applicant may submit an amendment to the Supplemental Register, and continue to argue entitlement to registration on the Principal Register in an appeal. An applicant may not, however, state that it "reserves the right" to amend to the Supplemental Register if the refusal is not withdrawn or is affirmed on appeal. In re Integrated Embedded, 120 USPQ2d 1504, 1511(TTAB 2016) (stating the "[a]pplicant cannot ‘reserve a right’ that does not exist").

If the applicant files a notice of appeal in such a case, the Board will institute the appeal, suspend action on the appeal and remand the application to the examining attorney to determine registrability on the Supplemental Register.

If the examining attorney determines that the applicant is entitled to registration on the Supplemental Register, the examining attorney must send a letter notifying the applicant of the acceptance of the amendment and telling the applicant that the application is being referred to the Board for resumption of the appeal. If the examining attorney determines that the applicant is not entitled to registration on the Supplemental Register, the examining attorney will issue a nonfinal action refusing registration on the Supplemental Register. If the applicant fails to overcome the refusal, the examining attorney will issue a final action, and refer the application to the Board to resume action on the appeal with respect to entitlement to registration on either the Principal or the Supplemental Register.

Rather than framing the issues in the alternative (i.e., whether the matter has acquired distinctiveness pursuant to §2(f) or, in the alternative, whether it is capable of registration on the Supplemental Register), the applicant may amend its application between the Principal and Supplemental Registers. 37 C.F.R. §2.75; see In re Educ. Commc'ns, Inc., 231 USPQ 787, 787 (TTAB 1986) ; In re Broco, 225 USPQ 227, 228 (TTAB 1984).

See TMEP §§816–816.05 and §1102.03 regarding amending an application to the Supplemental Register, and TBMP §1215 regarding alternative positions on appeal.

If the applicant specifically requests registration under §2(f), but the examining attorney considers the entire mark to be inherently distinctive and the claim of acquired distinctiveness to be unnecessary, the examining attorney must so inform the applicant and inquire whether the applicant wishes to delete the statement or to rely on it.

In this situation, if it is necessary to issue an Office action about another matter, the examining attorney must state in the Office action that the §2(f) claim appears to be unnecessary, and inquire as to whether the applicant wants to withdraw it. If it is otherwise unnecessary to communicate with the applicant, the inquiry may be made by telephone or email. If the applicant wants to delete the §2(f) claim, this may be done by examiner’s amendment. If the applicant does not respond promptly to the telephone or email message (applicant must be given at least three business days), the examining attorney must enter a Note to the File in the record and approve the application for publication without deleting the §2(f) claim.

If the applicant specifically requests registration of the entire mark under §2(f), but the examining attorney believes that part of the mark is inherently distinctive, the examining attorney should give the applicant the option of limiting the §2(f) claim to the matter that is not inherently distinctive, if otherwise appropriate. See TMEP §1212.02(f) regarding claims of §2(f) distinctiveness as to a portion of a mark. However, if the applicant wishes, a claim of acquired distinctiveness under §2(f) may be made as to an entire mark or phrase that contains both inherently distinctive matter and matter that is not inherently distinctive. In re Del E. Webb Corp., 16 USPQ2d 1232, 1234 (TTAB 1990) .

If the application contains statements that seem to relate to acquired distinctiveness or §2(f) but do not actually amount to a request for registration under §2(f), and the examining attorney does not believe that resorting to §2(f) is necessary, the examining attorney may treat the statements as surplusage. If it is necessary to communicate with the applicant about another matter, the examining attorney should inform the applicant that the statements are being treated as surplusage. If it is otherwise unnecessary to communicate with the applicant, the examining attorney should delete the statements from the Trademark database, enter a Note to the File in the record indicating that this has been done, and approve the application for publication. The documents containing the surplusage will remain in the record, but a §2(f) claim will not be printed in the Official Gazette or on the certificate of registration. See TMEP §817 regarding preparation of applications for publication or issuance.

Section 6(a) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1056(a), states, in part, "The Director may require the applicant to disclaim an unregistrable component of a mark otherwise registrable." See In re Creative Goldsmiths of Wash., Inc., 229 USPQ 766, 768 (TTAB 1986) ("[W]e conclude that it is within the discretion of an Examining Attorney to require the disclaimer of an unregistrable component (such as a common descriptive, or generic, name) of a composite mark sought to be registered on the Principal Register under the provisions of Section 2(f).").

A claim of acquired distinctiveness may apply to a portion of a mark (a claim of §2(f) "in part"). The standards for establishing acquired distinctiveness are the same whether a claim of distinctiveness pertains to the entire mark or a portion of it. However, examining attorneys must focus their review of the evidence submitted on the portion of the mark for which acquired distinctiveness is claimed, rather than on the entire mark.

Three basic types of evidence may be used to establish acquired distinctiveness for claims of §2(f) in part for a trademark or service mark:

These three basic types of evidence apply similarly to collective trademarks, collective service marks, and collective membership marks (together "collective marks"), and certification marks, with slight modifications regarding the type of evidence required due to (1) the different function and purpose of collective and certification marks and (2) the fact that these types of marks are used by someone other than the applicant. See 37 C.F.R. §2.41(b)-(d).

The applicant may submit one or any combination of these types of evidence. Depending on the nature of the relevant portion of the mark and the facts in the record, the examining attorney may determine that a claim of ownership of a prior registration(s) or a claim of five years’ substantially exclusive and continuous use in commerce is insufficient to establish a prima facie case of acquired distinctiveness in part.

The amount and character of evidence required typically depends on the facts of each case and the nature of the relevant portion of the mark sought to be registered. See Roux Labs., Inc. v. Clairol Inc., 427 F.2d 823, 829, 166 USPQ 34, 39 (C.C.P.A. 1970); In re Hehr Mfg. Co., 279 F.2d 526, 528, 126 USPQ 381, 383 (C.C.P.A. 1960) ; In re Gammon Reel, Inc., 227 USPQ 729, 730 (TTAB 1985) ; TMEP §1212.01. A determination regarding the acceptability of a §2(f) claim depends on the nature of the relevant portion of the mark and/or the nature and sufficiency of the evidence provided by the applicant. See In re La. Fish Fry Prods., Ltd., 797 F.3d 1332, 116 USPQ2d 1262 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (finding that applicant’s evidence of prior registrations did not establish that the specific wording at issue had acquired distinctiveness); TMEP §§1212.04(a), 1212.05(a), 1212.06.

The legal principles pertaining to evidence of acquired distinctiveness in part discussed below with respect to trademarks and service marks apply generally to collective marks and certification marks as well.

When a claim of acquired distinctiveness applies to a portion of a mark, the applicant must clearly identify the portion of the mark for which distinctiveness is claimed.

Generally, the element that is the subject of the §2(f) claim must present a separate and distinct commercial impression apart from the other elements of the mark. That is, it must be a separable element in order for the applicant to assert that it has acquired distinctiveness as a mark. Consequently, if a mark is unitary for purposes of avoiding a disclaimer, a claim of §2(f) in part would generally not be appropriate since the elements are so merged together that they cannot be regarded as separable. If appropriate, the applicant can claim §2(f) as to the entire unitary mark.

See TMEP §1212.09(b) regarding claims of §2(f) in part in §1(b) applications, and TMEP §1212.08 regarding claims of §2(f) in part in §44 and §66(a) applications.

See also TMEP §1212.10 for information on printing §2(f)-in-part notations and limitation statements.

Descriptive Matter Combined with an Inherently Distinctive Element

Claiming §2(f) in part is appropriate when descriptive matter that is combined with an inherently distinctive element, such as arbitrary words or an inherently distinctive design, presents a separate and distinct commercial impression apart from the other matter in the mark and has acquired distinctiveness through use by itself.

For example, if the mark is TASTY SNACKARAMA for potato chips and the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness as to the descriptive word TASTY by itself, the applicant must limit the claim under §2(f) to the word TASTY (i.e., "2(f) in part as to TASTY") since the term SNACKARAMA is inherently distinctive.

Similarly, if the mark is TASTY SNACKARAMA POTATO CHIPS for potato chips and the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness as to TASTY by itself, the applicant must limit the claim under §2(f) to the word TASTY (i.e., "2(f) in part as to TASTY") since the term SNACKARAMA is inherently distinctive. The applicant must also disclaim the generic wording POTATO CHIPS.

If the mark is TASTY POTATO CHIPS combined with an inherently distinctive design for potato chips and the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness as to the wording TASTY POTATO CHIPS by itself, the applicant must limit the claim under §2(f) to the wording TASTY POTATO CHIPS (i.e., "2(f) in part as to TASTY POTATO CHIPS"). The applicant must also disclaim the generic wording POTATO CHIPS. See In re Am. Furniture Warehouse CO, 126 USPQ2d 1400, 1407 (TTAB 2018) ("While a generic term standing alone certainly cannot acquire distinctiveness . . . the generic term may be included in the claim of acquired distinctiveness as long as an accompanying disclaimer of the generic term is provided.").

Alternatively, if the mark is TASTY POTATO CHIPS combined with an inherently distinctive design for potato chips and the applicant can only show acquired distinctiveness as to TASTY (e.g., because the applicant had not previously used the entire wording TASTY POTATO CHIPS), the applicant must limit the claim under §2(f) to the word TASTY (i.e., "2(f) in part as to TASTY"). The applicant must also disclaim the generic wording POTATO CHIPS.

Geographically Descriptive Matter Combined with an Inherently Distinctive Element

Claims of §2(f) in part are also appropriate when a mark is comprised of geographically descriptive matter combined with an inherently distinctive element, and the geographically descriptive matter presents a separate and distinct commercial impression apart from the other matter in the mark and has acquired distinctiveness through use by itself.

For example, if the mark is TEXAS GOLD for car-cleaning preparations and the applicant, who is based in Texas, can show acquired distinctiveness as to TEXAS by itself, the applicant must limit the claim under §2(f) to the word TEXAS only (i.e., "2(f) in part as to TEXAS") since the term GOLD is inherently distinctive.

Similarly, if the mark is TEXAS combined with an inherently distinctive design element for car-cleaning preparations and the applicant, who is again from Texas, can show acquired distinctiveness as to the wording in the mark, the applicant must limit the claim under §2(f) to the word TEXAS only (i.e., "2(f) in part as to TEXAS").

An applicant may claim §2(f) in part as to wording consisting of both geographically descriptive matter and generic matter if the applicant establishes that the combined wording as a whole has acquired distinctiveness and provides a disclaimer of the generic matter. See In re Am. Furniture Warehouse CO, 126 USPQ2d at 1407-08 (TTAB 2018) (accepting a §2(f)-in-part claim as to AMERICAN FURNITURE WAREHOUSE, provided that applicant disclaimed FURNITURE WAREHOUSE).

See TMEP §1210.07(b) for further information regarding the registrability of geographic terms under §2(f) in part.

Surname Combined with Generic Wording

Applicants may also claim §2(f) in part for marks comprised of a surname combined with generic wording, when the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness only as to the surname.

For example, if the mark is JONES JEANS for pants and the applicant can only show acquired distinctiveness as to JONES (because the applicant had not previously used the entire wording JONES JEANS, for example), the applicant must limit the claim under §2(f) to the surname JONES only (i.e., "2(f) in part as to JONES"). The applicant must also disclaim the generic wording JEANS. However, this situation is rare, and the record must clearly reflect that the applicant can only show acquired distinctiveness as to the claimed portion of the mark. Note, by contrast, that if the applicant’s prior use is of the entire mark, JONES JEANS, a claim of §2(f) in part would be incorrect because the claim of acquired distinctiveness should apply to the entire mark. That is, in this example, the proper claim would be §2(f) as to JONES JEANS with a separate disclaimer of JEANS.

As an Alternative to a Disclaimer

A claim of §2(f) in part may be offered as an alternative to a disclaimer requirement, if it appears that the applicant can establish acquired distinctiveness in the relevant portion of the mark.

For example, if the mark is MOIST MORSELS combined with an inherently distinctive design for various food items, the applicant must enter a disclaimer of MOIST MORSELS or, if appropriate, a claim of §2(f) in part as to MOIST MORSELS. Any generic matter included in such a claim must still be disclaimed. See In re Am. Furniture Warehouse CO, 126 USPQ2d at 1407-08.

Examining attorneys are not required to offer the applicant the option of claiming §2(f) in part when issuing a disclaimer requirement. However, it is not uncommon for an applicant to respond to a disclaimer requirement with a claim of §2(f) in part instead of the required disclaimer, and this option may be offered in the first Office action, if appropriate.

Claim Applies to Entire Mark

When a mark is comprised of merely descriptive matter, geographically descriptive matter, or a surname combined with generic matter, and the applicant has made a prima facie case of acquired distinctiveness, the applicant’s §2(f) claim should generally refer to the entire mark as used, with a separate disclaimer of any generic or otherwise unregistrable component. See In re Am. Furniture Warehouse CO, 126 USPQ2d 1400, 1407 (TTAB 2018) ("[A] generic term may be included in the claim of acquired distinctiveness as long as an accompanying disclaimer of the generic term is provided."). See TMEP §1212.02(f)(ii)(A) regarding including generic matter in §2(f)-in-part claims.

For example, if the mark is NATIONAL CAR RENTAL for car-rental services and the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness as to the entire mark, the proper claim is §2(f) as to NATIONAL CAR RENTAL with a separate disclaimer of the generic wording CAR RENTAL. Similarly, if the mark is NATIONAL CAR RENTAL combined with an inherently distinctive design element, and the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness as to the entire wording, the proper §2(f) statement is §2(f) in part as to the wording NATIONAL CAR RENTAL with a separate disclaimer of CAR RENTAL. In these examples, it would be improper to limit the §2(f) statement to the word NATIONAL because the applicant is not claiming acquired distinctiveness as to NATIONAL, but rather as to the wording NATIONAL CAR RENTAL.

However, if the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness only as to the word NATIONAL (e.g., because the applicant had not previously used the entire wording NATIONAL CAR RENTAL), the applicant may claim §2(f) in part as to NATIONAL and must separately disclaim CAR RENTAL. Similarly, if the mark is NATIONAL CAR RENTAL combined with an inherently distinctive design element, and the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness only as to the word NATIONAL, the proper §2(f) statement is §2(f) in part as to the word NATIONAL with a separate disclaimer of CAR RENTAL. This situation is rare, and the record must clearly reflect that the applicant can show acquired distinctiveness only as to the claimed portion of the mark.

If a §2(f)-in-part claim is improperly provided by the applicant when the record reflects that the §2(f) claim should apply to the entire mark, or vice versa, the examining attorney must issue a new requirement to correct the §2(f) claim. See TMEP §§1212.05(d) and 1212.07 regarding verification of amended §2(f) claims based on five years’ use.

Inappropriate Alternative to a Disclaimer

In some situations, §2(f) in part is not an acceptable alternative to a disclaimer requirement. Specifically, if an applicant’s claim of distinctiveness applies to only part of a mark and the examining attorney determines that (1) the claimed portion of the mark is unregistrable (e.g., generic) and therefore the §2(f) claim is of no avail or (2) although the claimed portion is registrable, the applicant has failed to establish acquired distinctiveness, the examining attorney may require a disclaimer of that portion of the mark, assuming a disclaimer is otherwise appropriate. See In re Lillian Vernon Corp., 225 USPQ 213 (TTAB 1985) (affirming requirement for disclaimer of PROVENDER in application to register PROVENDER and design for "mail order services in the gourmet, bath and gift item field," "provender" meaning "food" (claim of §2(f) distinctiveness in part held unacceptable)) ; cf. In re Chopper Indus.,222 USPQ 258 (TTAB 1984) (reversing requirement for disclaimer of CHOPPER in application to register CHOPPER 1 and design for wood log splitting axes (claim of §2(f) distinctiveness in part held acceptable)).

Relying on a Claim of Ownership of a Prior Registration

In certain cases, an applicant may not rely on ownership of one or more prior registrations on the Principal Register of the relevant portion of the mark, for goods or services that are the same as or related to those named in the pending application, to support a claim of §2(f) in part.

First, if the term for which the applicant seeks to prove distinctiveness was disclaimed in the claimed prior registration, the prior registration may not be accepted as prima facie evidence of acquired distinctiveness. See Kellogg Co. v. Gen. Mills, Inc., 82 USPQ2d 1766, 1771 n.5 (TTAB 2007) ; In re Candy Bouquet Int’l, Inc., 73 USPQ2d 1883, 1889-90 (TTAB 2004) ; TMEP §1212.04(a). For example, if the mark is TASTY SNACKARAMA for potato chips and the applicant attempts to rely on a prior registration for the mark TASTY combined with an inherently distinctive design, with TASTY disclaimed, for the same goods, to support its claim of acquired distinctiveness as to the descriptive word TASTY, such evidence would not be sufficient since the word TASTY was disclaimed in the prior registration. Absent additional evidence to show acquired distinctiveness as to TASTY, the examining attorney must require the applicant to delete the claim of §2(f) in part, and instead provide a disclaimer of the term TASTY.

Second, when an applicant is claiming §2(f) in part as to only a portion of its mark, the mark in the claimed prior registration must be the same as or the legal equivalent of the portion of the mark for which the applicant is claiming acquired distinctiveness. A mark is the legal equivalent of a portion of another mark if it creates the same, continuing commercial impression such that the consumer would consider the mark to be the same as the portion of the other mark. See TMEP §1212.04(b) and cases cited therein.

§2(f) in Part versus §2(f) Claim Restricted to Particular Goods, Services, or Classes

A claim of §2(f) in part should not be confused with a §2(f) claim restricted to certain classes in a multiple-class application or to a portion of the goods/services within a single class. Such a restriction can be made regardless of whether the applicant is claiming §2(f) for the entire mark or §2(f) in part for a portion of the mark. See TMEP §1212.02(j).

In a first action refusing registration, the examining attorney should suggest, where appropriate, that the applicant amend its application to seek registration under §2(f). For example, this should be done as a matter of course, if otherwise appropriate, in cases where registration is refused under §2(e)(4) on the ground that the mark is primarily merely a surname, and the applicant has recited dates of use that indicate that the mark has been in use in commerce for at least five years.

If the examining attorney determines that an applicant’s evidence is insufficient to establish that the mark has acquired distinctiveness, the examining attorney should suggest, where appropriate, that the applicant submit additional evidence. See In re Half Price Books, Records, Magazines, Inc., 225 USPQ 219, 220 n.2 (TTAB 1984) (Noting that applicant was specifically invited to seek registration pursuant to §2(f) but, after amending its application to do so, was refused registration on the ground that the mark was incapable of acquiring distinctiveness, the Board stated that, in fairness to applicant, this practice should be avoided where possible).

The examining attorney should not "require" that the applicant submit evidence of secondary meaning. There would be no practical standard for a proper response to this requirement, nor would there be a sound basis for appeal from the requirement. See In re Capital Formation Counselors, Inc., 219 USPQ 916, 917 n.2 (TTAB 1983) ("Section 2(f) is not a provision on which registration can be refused.").

The examining attorney should not specify the kind or the amount of evidence sufficient to establish that a mark has acquired distinctiveness. It is the responsibility of the applicant to submit evidence to establish that the mark has acquired distinctiveness. See TMEP §1212.01. However, the examining attorney may make a suggestion as to a course of action, if the examining attorney believes this would further the prosecution of the application.

If an application is filed under §2(f) of the Trademark Act and the examining attorney determines that (1) the mark is not inherently distinctive, and (2) the applicant’s evidence of secondary meaning is insufficient to establish that the mark has acquired distinctiveness, the examining attorney will issue a nonfinal action refusing registration on the Principal Register pursuant to the appropriate section of the Trademark Act (e.g., §2(e)(1)), and will separately explain why the applicant’s evidence of secondary meaning is insufficient to overcome the underlying statutory basis for refusal. The examining attorney should suggest, where appropriate, that the applicant submit additional evidence. See TMEP §1212.02(g) concerning the examining attorney’s role in suggesting a claim of distinctiveness under §2(f).

If an application is not filed under §2(f) and the examining attorney determines that the mark is not inherently distinctive, the examining attorney will issue a nonfinal action refusing registration on the Principal Register under the appropriate section of the Act (e.g., §2(e)(1)). The examining attorney should suggest, where appropriate, that the applicant amend its application to claim distinctiveness under §2(f).

Thereafter, if the applicant amends its application to seek registration under §2(f), a new issue is raised as to the sufficiency of the applicant’s evidence of secondary meaning (see TMEP §714.05(a)(i)). The underlying statutory basis for refusal remains the same (i.e., §2(e)(1)), but the issue changes from whether the underlying refusal is warranted to whether the matter has acquired distinctiveness. If the examining attorney is persuaded that a prima facie case of acquired distinctiveness has been established, the examining attorney will approve the application for publication under §2(f). If the examining attorney determines that the applicant’s evidence is insufficient to establish that the matter has acquired distinctiveness, the examining attorney will issue a second nonfinal action repeating the underlying statutory basis for refusal (e.g., §2(e)(1)), and explaining why the applicant’s evidence is insufficient to overcome the stated refusal.

The examining attorney cannot issue a final refusal on the underlying statutory basis of the original refusal, upon an applicant’s initial assertion of a §2(f) claim. The mere assertion of distinctiveness under §2(f) raises a new issue. See In re Educ. Commc’ns, Inc., 231 USPQ 787, 787 n.2 (TTAB 1986) . Even if the applicant has submitted, in support of the §2(f) claim, a statement of five years’ use that is technically defective (e.g., not verified or comprising incorrect language), the assertion of §2(f) distinctiveness still constitutes a new issue.

Exception: The examining attorney may issue a final refusal upon an applicant’s initial assertion of a §2(f) claim if the amendment is irrelevant to the outstanding refusal. See TMEP §714.05(a)(i). See also TMEP §§1212.02(a) and 1212.02(i) regarding situations where it is and is not appropriate to submit a claim of acquired distinctiveness to overcome a refusal.

After the examining attorney has issued a nonfinal action refusing registration on the Principal Register with a finding that the applicant’s evidence of secondary meaning is insufficient to overcome the stated refusal, the applicant may elect to submit additional arguments and/or evidence regarding secondary meaning. If, after considering this submission, the examining attorney is persuaded that the applicant has established a prima facie case of acquired distinctiveness, the examining attorney will approve the application for publication under §2(f). If the examining attorney is not persuaded that the applicant has established a prima facie case of acquired distinctiveness, and the application is otherwise in condition for final refusal, the examining attorney will issue a final refusal pursuant to the appropriate section of the Act (e.g., §2(e)(1)), with a finding that the applicant’s evidence of acquired distinctiveness is insufficient to overcome the stated refusal. See In re Capital Formation Counselors, Inc., 219 USPQ 916, 917 n.2 (TTAB 1983) .

In any action in which the examining attorney indicates that the evidence of record is insufficient to establish that the mark has acquired distinctiveness, the examining attorney must specify the reasons for this determination. See In re Interstate Folding Box Co., 167 USPQ 241, 243 (TTAB 1970); In re H. A. Friend & Co., 158 USPQ 609, 610 (TTAB 1968).

If matter is generic, functional, or purely ornamental, or otherwise fails to function as a mark, the matter is unregistrable. See, e.g., In re Bongrain Int’l Corp., 894 F.2d 1316, 1317 n.4, 13 USPQ2d 1727, 1728 n.4 (Fed. Cir. 1990) ("If a mark is generic, incapable of serving as a means ‘by which the goods of the applicant may be distinguished from the goods of others’ . . . it is not a trademark and can not be registered under the Lanham Act."); H. Marvin Ginn Corp. v. Int'l Ass’n of Fire Chiefs, Inc., 782 F.2d 987, 989, 228 USPQ 528, 530 (Fed. Cir. 1986), and cases cited therein ("A generic term . . . can never be registered as a trademark because such a term is ‘merely descriptive’ within the meaning of §2(e)(1) and is incapable of acquiring de jure distinctiveness under §2(f). The generic name of a thing is in fact the ultimate in descriptiveness."); see also In re Melville Corp., 228 USPQ 970, 972 (TTAB 1986) (finding BRAND NAMES FOR LESS, for retail store services in the clothing field, "should remain available for other persons or firms to use to describe the nature of their competitive services.").

It is axiomatic that matter may not be registered unless it is used as a mark, namely, "in a manner calculated to project to purchasers or potential purchasers a single source or origin for the goods in question." In re Remington Prods. Inc., 3 USPQ2d 1714, 1715 (TTAB 1987) . See, e.g., In re Melville Corp., 228 USPQ at 971 n.2 ("If matter proposed for registration does not function as a mark, it is not registrable in accordance with Sections 1 and 2 of the Act because the preambles of those sections limit registration to subject matter within the definition of a trademark."); In re Whataburger Sys., Inc.,209 USPQ 429, 430 (TTAB 1980) ("[A] designation may not be registered either as a trademark or as a service mark unless it is used as a mark, in such a manner that its function as an indication of origin may be readily perceived by persons encountering the goods or services in connection with which it is used.").

Therefore, where the examining attorney has determined that matter sought to be registered is not registrable because it is not a mark within the meaning of the Trademark Act, a claim that the matter has acquired distinctiveness under §2(f) as applied to the applicant’s goods or services does not overcome the refusal. See, e.g., TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 33, 58 USPQ2d 1001, 1007 (2001) ("Functionality having been established, whether MDI’S dual spring design has acquired secondary meaning need not be considered."); In re R.M. Smith, Inc., 734 F.2d 1482, 1484-85, 222 USPQ 1, 3 (Fed. Cir. 1984) ("Evidence of distinctiveness is of no avail to counter a de jure functionality rejection."); Stuart Spector Designs, Ltd. v. Fender Musical Instruments Corp., 94 USPQ2d 1549, 1554 (TTAB 2009) (stating that a product design may become generic and, thus, cannot be registered, regardless of applicant’s claim of acquired distinctiveness); In re Tilcon Warren, Inc., 221 USPQ 86, 88 (TTAB 1984) ("Long use of a slogan which is not a trademark and would not be so perceived does not, of course, transform the slogan into a trademark."); In re Mancino,219 USPQ 1047, 1048 (TTAB 1983) ("Since the refusal . . . was based on applicant’s failure to demonstrate technical service mark use, the claim of distinctiveness under Section 2(f) was of no relevance to the issue in the case.").

As discussed above, evidence of acquired distinctiveness will not alter the determination that matter is unregistrable. However, the examining attorney must review the evidence and make a separate, alternative, determination as to whether, if the proposed mark is ultimately determined to be capable, the applicant’s evidence is sufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness. This will provide a more complete record in the event that the applicant appeals and prevails on the underlying refusal. The examining attorney must also consider whether the applicant’s evidence has any bearing on the underlying refusal. See TMEP §§1209.02–1209.02(b) regarding the procedure for descriptiveness and/or generic refusals.

If the examining attorney fails to separately address the sufficiency of the §2(f) evidence, this may be treated as a concession that the evidence would be sufficient to establish distinctiveness if the mark is ultimately found to be capable. Cf. In re Dietrich,91 USPQ2d 1622, 1625 (TTAB 2009), in which the Board held that an examining attorney had "effectively conceded that, assuming the mark is not functional, applicant’s evidence is sufficient to establish that the mark has acquired distinctiveness," where the examining attorney rejected the applicant’s §2(f) claim on the ground that applicant’s bicycle wheel configuration was functional and thus unregistrable even under §2(f), but did not specifically address the sufficiency of the §2(f) evidence or the question of whether the mark would be registrable under §2(f) if it were ultimately found to be nonfunctional.

See also In re Wakefern Food Corp., 222 USPQ 76, 79 (TTAB 1984) (finding applicant’s evidence relating to public perception of WHY PAY MORE! entitled to relatively little weight, noting that the evidence is relevant to the issue of whether the slogan functions as a mark for applicant’s supermarket services).

An applicant may claim acquired distinctiveness as to certain classes in a multiple-class application, or as to only a portion of the goods/services within a single class. The applicant must clearly identify the goods/services/classes for which distinctiveness is claimed. The standards for establishing acquired distinctiveness are the same whether the claim of distinctiveness pertains to all or to only a portion of the goods/services.

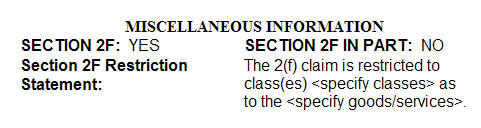

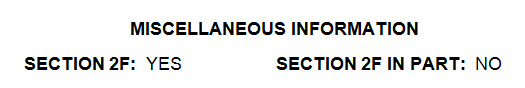

If the examining attorney determines that a claim of distinctiveness as to a portion of the goods/services/classes is appropriate, the examining attorney must ensure that the "§2(f)" field in the Trademark database indicates that the §2(f) claim is restricted to certain goods/services/classes, and that those goods/services/classes are clearly identified in the restriction statement of record in the USPTO database. See the following example, where the applicant is claiming §2(f) for the entire mark, but only as to a portion of the goods/services:

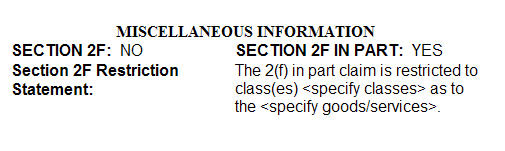

See also the following example, where the applicant is claiming §2(f) in part (not as to the entire mark), restricted to a portion of the goods/services:

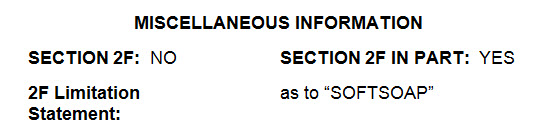

A separate limitation statement is also required for claims of §2(f) in part. See TMEP §1212.10.

See also 37 C.F.R. §2.41(b)-(d) (for collective and certification marks).

"To establish secondary meaning, a manufacturer must show that, in the minds of the public, the primary significance of a product feature or term is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself." Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 851 n.11, 214 USPQ 1, 4 n.11 (1982).

Trademark Rule 2.41(a)(1), 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(1), provides that the examining attorney may accept, as prima facie evidence of acquired distinctiveness, ownership by the applicant of one or more active prior registrations of the same mark on the Principal Register or under the Act of 1905. See TMEP §1212.04(b) as to what constitutes the "same mark," and TMEP §§1212.09–1212.09(b) concerning §1(b) applications.

The rule states that, "in appropriate cases," ownership of existing registrations to establish acquired distinctiveness "may be accepted as sufficient prima facie evidence of distinctiveness," but that the USPTO may, at its option, require additional evidence of distinctiveness. In re La. Fish Fry Prods., Ltd., 797 F.3d 1332, 116 USPQ2d 1262 (Fed. Cir. 2015); In re Dial-A-Mattress Operating Corp., 240 F.3d 1341, 1347, 57 USPQ2d 1807, 1812 (Fed. Cir. 2001); In re Loew’s Theatres, Inc., 769 F.2d 764, 769, 226 USPQ 865, 869 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

The following are general guidelines regarding claiming ownership of prior registrations as a method of establishing acquired distinctiveness.

The examining attorney has the discretion to determine whether the nature of the mark sought to be registered is such that a claim of ownership of an active prior registration on the Principal Register for sufficiently similar goods or services is enough to establish acquired distinctiveness. For example, if the mark sought to be registered is deemed to be highly descriptive or misdescriptive of the goods or services named in the application, the examining attorney may require additional evidence of acquired distinctiveness. See In re Loew’s Theatres, Inc., 769 F.2d 764, 769, 226 USPQ 865, 869 (Fed. Cir. 1985); In re Guaranteed Rate, Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 10869, at *9 (TTAB 2020); In re Cordua Rests. LP, 110 USPQ2d 1227, 1234 (TTAB 2014), aff’d, 823 F.3d 594, 118 USPQ2d 1632 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

If the term for which the applicant seeks to prove distinctiveness was disclaimed in the prior registration, the prior registration may not be accepted as prima facie evidence of acquired distinctiveness. Kellogg Co. v. Gen. Mills, Inc., 82 USPQ2d 1766, 1771 n.5 (TTAB 2007); In re Candy Bouquet Int’l, Inc., 73 USPQ2d 1883, 1889-90 (TTAB 2004).

A proposed mark is the "same mark" as a previously registered mark for the purpose of 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(1) if it is the "legal equivalent" of such a mark. "A mark is the legal equivalent of another if it creates the same, continuing commercial impression such that the consumer would consider them both the same mark." In re Dial-A-Mattress Operating Corp., 240 F.3d 1341, 1347, 57 USPQ2d 1807, 1812 (Fed. Cir. 2001); see also In re Brouwerij Bosteels, 96 USPQ2d 1414, 1423 (TTAB 2010) (finding three-dimensional product packaging trade dress mark is not the legal equivalent of a two-dimensional design logo); In re Nielsen Bus. Media, Inc., 93 USPQ2d 1545, 1547-48 (TTAB 2010) (finding THE BOLLYWOOD REPORTER is not the legal equivalent of the registered marks THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, THEHOLLYWOODREPORTER.COM, and THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER STUDIO BLU-BOOK); In re Binion, 93 USPQ2d 1531, 1539 (TTAB 2009) (finding BINION and BINION’S are not the legal equivalents of the registered marks JACK BINION and JACK BINION’S); Bausch & Lomb Inc. v. Leupold & Stevens Inc., 6 USPQ2d 1475, 1477 (TTAB 1988) ("The words GOLDEN RING, while they are used to describe the device, are by no means identical to or substantially identical to the gold ring device trademark."); In re Best Prods. Co., 231 USPQ 988, 989 n.6 (TTAB 1986) ("[W]e infer in the instant case that the differences between the marks BEST & Des. and BEST JEWELRY & Des., and between the identifications of services in their respective registrations, were deemed to be immaterial differences."); In re Loew’s Theatres, Inc., 223 USPQ 513, 514 n.5 (TTAB 1984) , aff’d, 769 F.2d 764, 226 USPQ 865 (Fed. Cir. 1985) ("We do not, however, agree with the Examining Attorney that a minor difference in the marks (i.e., here, merely that the mark of the existing registration is in plural form) is a proper basis for excluding any consideration of this evidence under the rule."); In re Flex-O-Glass, Inc., 194 USPQ 203, 205-06 (TTAB 1977) ("[P]ersons exposed to applicant’s registered mark . . . would, upon encountering [applicant’s yellow rectangle and red circle design] . . ., be likely to accept it as the same mark or as an inconsequential modification or modernization thereof . . . . [A]pplicant may ‘tack on’ to its use of the mark in question, the use of the registered mark . . . and therefore may properly rely upon its registration in support of its claim of distinctiveness herein.").

See, e.g., Van Dyne-Crotty, Inc. v. Wear-Guard Corp., 926 F.2d 1156, 1159, 17 USPQ2d 1866, 1868 (Fed. Cir. 1991) regarding the concept of "tacking" with reference to prior use of a legally equivalent mark.

When an applicant is claiming §2(f) as to only a portion of its mark, then the previously registered mark must be the legal equivalent of the relevant portion for which the applicant is claiming acquired distinctiveness. See TMEP §1212.02(f) regarding claims of acquired distinctiveness as to a portion of a mark.

The examining attorney must determine whether the goods or services identified in the application are "sufficiently similar" to the goods or services identified in the active prior registration(s) on the Principal Register. See 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(1). If the similarity or relatedness is self-evident, the examining attorney may generally accept the §2(f) claim without additional evidence. This is most likely to occur with ordinary consumer goods or services where the nature and function or purpose of the goods or services is commonly known and readily apparent (e.g., a prior registration for hair shampoo and new application for hair conditioner).

If the similarity or relatedness of the goods or services in the application and prior registration(s) is not self-evident, the examining attorney may not accept the §2(f) claim without evidence and an explanation demonstrating the purported similarity or relatedness between the goods or services. This is likely to occur with industrial goods or services where there may in fact be a high degree of similarity or relatedness, but it would not be obvious to someone who is not an expert in the field. See Bausch & Lomb Inc. v. Leupold & Stevens Inc., 6 USPQ2d 1475, 1478 (TTAB 1988) ("Applicant’s almost total reliance on the distinctiveness which its gold ring device has achieved vis-à-vis rifle scopes and handgun scopes is simply not sufficient by itself to establish that the same gold ring device has become distinctive vis-à-vis binoculars and spotting scopes."); In re Best Prods. Co., 231 USPQ 988, 989 n.6 (TTAB 1986) ("[W]e infer in the instant case that the differences between the marks BEST & Des. and BEST JEWELRY & Des., and between the identifications of services in their respective registrations [‘mail order and catalog showroom services’ and ‘retail jewelry store services’], were deemed to be immaterial differences."); In re Owens-Illinois Glass Co., 143 USPQ 431, 432 (TTAB 1964) (holding applicant’s ownership of prior registration of LIBBEY for cut-glass articles acceptable as prima facie evidence of distinctiveness of identical mark for plastic tableware, the Board stated, "Cut-glass and plastic articles of tableware are customarily sold in the same retail outlets, and purchasers of one kind of tableware might well be prospective purchasers of the other."); In re Lytle Eng'g & Mfg. Co., 125 USPQ 308, 309 (TTAB 1960) (holding applicant’s ownership of prior registration of LYTLE for various services, including the planning, preparation, and production of technical publications, acceptable as prima facie evidence of distinctiveness of identical mark for brochures, catalogs, and bulletins).

Trademark Rule 2.41(a)(1), 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(1), states that ownership of an active prior registration "on the Principal Register or under the Act of 1905" may be accepted as prima facie evidence of distinctiveness. Therefore, claims of acquired distinctiveness under §2(f) may not be based on ownership of registrations on the Supplemental Register. See In re Canron, Inc., 219 USPQ 820, 822n.2 (TTAB 1983).

Additionally, a claim of acquired distinctiveness may not be based on a registration that is cancelled or expired. See 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(1); In re Info. Builders, Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 10444, at *6 n.19 (TTAB 2020); In re BankAmerica Corp., 229 USPQ 852, 853 (TTAB 1986) . When an examining attorney considers a §2(f) claim based on ownership of one or more prior registrations, the examining attorney must confirm, in the records of the USPTO, that the claimed registrations were issued on the Principal Register or under the Act of 1905 and that they are in full force and effect.

The following language may be used to claim distinctiveness under §2(f) for a trademark or service mark on the basis of ownership of one or more prior registrations:

The mark has become distinctive of the goods and/or services as evidenced by ownership of active U.S. Registration No(s). __________ on the Principal Register for the same mark for sufficiently similar goods and/or services.

If the applicant is relying solely on its ownership of one or more active prior registrations on the Principal Register as proof of acquired distinctiveness, the §2(f) claim does not have to be verified. Therefore, an applicant or an applicant’s attorney may authorize amendment of an application to add such a claim through an examiner’s amendment, if otherwise appropriate.

Section 2(f) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(f), provides that "proof of substantially exclusive and continuous use" of a designation "as a mark by the applicant in commerce for the five years before the date on which the claim of distinctiveness is made" may be accepted as prima facie evidence that the mark has acquired distinctiveness as used in commerce with the applicant’s goods or services. See 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(2).

The Trademark Act previously required that the relevant five-year period precede the filing date of the application. The Trademark Law Revision Act of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-667, 102 Stat. 3935 (1988), revised §2(f) of the Act to provide for a prima facie showing of acquired distinctiveness based on five years’ use running up to the date the claim is made. Under the revised provision, any five-year claim submitted on or after November 16, 1989, is subject to the new time period. This applies even if the application was filed prior to that date.

Section 2(f) of the Act and 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(2) state that reliance on a claim of five years’ use to establish acquired distinctiveness "may" be acceptable in "appropriate cases." The USPTO may, at its option, require additional evidence of distinctiveness. In re La. Fish Fry Prods., Ltd., 797 F.3d 1332, 1336-37, 116 USPQ2d 1262, 1265 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (noting that the statute does not require the USPTO to accept five years’ use as prima facie evidence of acquired distinctiveness). Whether a claim of five years’ use will be deemed sufficient to establish that the mark has acquired distinctiveness depends largely on the nature of the mark in relation to the specified goods, services, or classes.

The following are general guidelines regarding the statutorily suggested proof of five years’ use as a method of establishing acquired distinctiveness.

For most surnames, the statement of five years’ use will be sufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness.

For marks refused under §2(e)(1) or §2(e)(2), the amount of evidence necessary to establish secondary meaning varies. "[T]he greater the degree of descriptiveness the term has, the heavier the burden to prove it has attained secondary meaning." In re Bongrain Int’l Corp., 894 F.2d 1316, 1317 n.4, 13 USPQ2d 1727, 1728 n.4 (Fed. Cir. 1990) (citing Yamaha Int’l Corp. v. Hoshino Gakki Co., 840 F.2d 1572, 1581, 6 USPQ2d 1001, 1008 (Fed. Cir. 1988)); see also Royal Crown Co. v. Coca-Cola Co., 892 F.3d 1358, 1368-69, 127 USPQ2d 1041, 1047 (Fed. Cir. 2018). For terms with a greater degree of descriptiveness, statements of length of use alone generally will not be sufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness. See, e.g., In re La. Fish Fry Prods., Ltd., 797 F.3d 1332, 1336-37, 116 USPQ2d 1262, 1265 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (holding that the Board was within its discretion not to accept applicant’s allegation of five years’ use given the highly descriptive nature of the mark); Spiritline Cruises LLC v. Tour Mgmt. Servs. Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 48324, at *11 (TTAB 2020) (holding applicant’s claim of use since 2003 not sufficient to show the mark CHARLESTON HARBOR TOURS had become distinctive because the term was highly geographically descriptive); In re Yarnell Ice Cream, LLC, 2019 USPQ2d 265039, at *10-11 (TTAB 2019) (holding applicant’s claim of use since 2012 not sufficient to show the mark SCOOP had become distinctive for ice cream because other circumstances undercut the significance of this claim of extended use); In re Virtual Indep. Paralegals, LLC, 2019 USPQ2d 111512, at *11-12 (TTAB 2019) (holding applicant’s claim of use for the last five years not sufficient to show the mark VIRTUAL INDEPENDENT PARALEGALS had become distinctive for various paralegal services due to the highly descriptive nature of the proposed mark); Apollo Med. Extrusion Techs., Inc. v. Med. Extrusion Techs., Inc., 123 USPQ2d 1844, 1856 (TTAB 2017) (finding, despite applicant’s claim of use since 1991, that much more evidence, especially in the quantity of direct evidence from the relevant purchasing public, would be necessary to show that the designation MEDICAL EXTRUSION TECHNOLOGIES has become distinctive for Applicant’s medical extrusion goods); In re Crystal Geyser Water Co., 85 USPQ2d 1374 (TTAB 2007) (holding applicant’s evidence of acquired distinctiveness, including a claim of use since 1990, sales of more than 7,650,000,000 units of its goods, and extensive display of its mark CRYSTAL GEYSER ALPINE SPRING WATER on advertising and delivery trucks and promotional paraphernalia, insufficient to establish that the highly descriptive phrase ALPINE SPRING WATER had acquired distinctiveness for applicant’s bottled spring water); In re Kalmbach Publ’g Co., 14 USPQ2d 1490 (TTAB 1989) (holding applicant’s sole evidence of acquired distinctiveness, a claim of use since 1975, insufficient to establish that the highly descriptive, if not generic, designation RADIO CONTROL BUYERS GUIDE had become distinctive of applicant’s magazines).

For matter that is not inherently distinctive because of its nature (e.g., nondistinctive product design, overall color of a product, mere ornamentation, and sounds for goods that make the sound in their normal course of operation), evidence of five years’ use is not sufficient to show acquired distinctiveness. In such a case, actual evidence that the mark is perceived as a mark for the relevant goods, services, or classes would be required to establish distinctiveness. See generally In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp., 774 F.2d 1116, 227 USPQ 417 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (color pink as uniformly applied to applicant’s fibrous glass residential insulation); In re R.M. Smith, Inc., 734 F.2d 1482, 222 USPQ 1 (Fed. Cir. 1984) (configuration of pistol grip water nozzle for water nozzles); Nextel Commc’ns, Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., 91 USPQ2d 1393, 1401 (TTAB 2009) (noting that "the evidence required is in proportion to the degree of nondistinctiveness of the mark at issue" in relation to a sound mark emitted by cellular telephones in their normal course of operation); In re ic! berlin brillen GmbH, 85 USPQ2d 2021 (TTAB 2008) (configuration of an earpiece for frames for sunglasses and spectacles comprised of three "fingers" near the hinge); In re Black & Decker Corp., 81 USPQ2d 1841, 1844 (TTAB 2006) (finding applicant successfully established acquired distinctiveness for the design of a key head for key blanks and various metal door hardware, where evidence submitted in support included twenty-four years of use in commerce and significant evidence regarding industry practice, such that the evidence showed that "it is common for manufacturers of door hardware to use key head designs as source indicators."); Edward Weck Inc. v. IM Inc., 17 USPQ2d 1142 (TTAB 1990) (color green for medical instruments); In re Cabot Corp., 15 USPQ2d 1224 (TTAB 1990) (configuration of a pillow-pack container for ear plugs and configuration of a pillow-pack container with trade dress (white circle surrounded by blue border) for ear plugs); In re Star Pharm., Inc., 225 USPQ 209 (TTAB 1985) (color combination of drug capsule and seeds therein for methyltestosterone); In re Craigmyle, 224 USPQ 791 (TTAB 1984) (configuration of halter square for horse halters).

The five years of use in commerce does not have to be exclusive, but must be "substantially" exclusive. 15 U.S.C. §1052(f); 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(2). This makes allowance for use by others that may be inconsequential or infringing, which does not necessarily invalidate the applicant’s claim. L.D. Kichler Co. v. Davoil, Inc., 192 F.3d 1349, 1352, 52 USPQ2d 1307, 1309 (Fed. Cir. 1999). Thus, when evaluating whether an applicant has had "substantially" exclusive use of a mark, the determination is based on "whether any use by a third party [is] ‘significant’ or whether it [is] merely ‘inconsequential or infringing.’" Galperti, Inc. v. Galperti S.R.L., 17 F.4th 1144, 1147, 2021 USPQ2d 1115, at *2 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

The existence of other applications to register the same mark, or other known uses of the mark, does not automatically eliminate the possibility of using this method of proof, but the examining attorney should inquire as to the nature of such use and be satisfied that it is not significant or does not otherwise nullify the claim of distinctiveness. See Galperti, Inc., 17 F.4th at 1148, 2021 USPQ2d 1115, at *4 ("a significant amount of marketplace use of a term not as a source identifier for those users does tend to undermine an applicant’s assertion that its own use has been substantially exclusive"); Levi Strauss & Co. v. Genesco, Inc., 742 F.2d 1401, 1403, 222 USPQ 939, 940-41 (Fed. Cir. 1984) ("When the record shows that purchasers are confronted with more than one (let alone numerous) independent users of a term or device, an application for registration under Section 2(f) cannot be successful, for distinctiveness on which purchasers may rely is lacking under such circumstances."); In re Jasmin Larian, LLC, 2022 USPQ2d 290, at *40-41 (TTAB 2022) (finding "the widespread use, sale of and discussions/comments about bamboo handbag designs similar to [a]pplicant’s applied-for mark" showed that "[a]pplicant’s use [was] not 'substantially exclusive'"); In re Dimarzio, Inc., 2021 USPQ2d 1191, at *13-25 (TTAB 2021) (finding the examining attorney's evidence of extensive third-party use of applicant's proposed color mark on the same goods showed that applicant's use was not substantially exclusive); Spiritline Cruises LLC v. Tour Mgmt. Servs. Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 48324, at *11 (TTAB 2020) (finding "the substantially non-exclusive use of CHARLESTON HARBOR TOURS . . . interfere[d] with the relevant public’s perception of the designation as an indicator of a single source"); In re MK Diamond Prods., Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 10882, at *21 (TTAB 2020) ("[w]hile absolute exclusivity is not required for a Section 2(f) registration, . . . the widespread use of other substantially similar [designs] . . . is inconsistent with the ‘substantially exclusive’ use required by the statute"); Milwaukee Elec. Tool Corp. v. Freud Am., Inc., 2019 USPQ2d 460354, at *25 (TTAB 2019) (finding evidence of third-party use of the proposed mark showed that registrant’s use had not been "substantially exclusive either at the time of registration or thereafter"); In re Gen. Mills IP Holdings II, LLC, 124 USPQ2d 1016, 1024 (TTAB 2017) (finding that "the presence in the market of yellow-packaged cereals from various sources . . . would tend to detract from any public perception of the predominantly yellow background as a source-indicator pointing solely to Applicant"); Ayoub, Inc. v. ACS Ayoub Carpet Serv., 118 USPQ2d 1392, 1404 (TTAB 2016) (finding that, because of widespread third-party uses of the surname Ayoub in connection with rug, carpet and flooring businesses, applicant's use of the applied-for mark, AYOUB, was not "substantially exclusive" and thus the mark had not acquired distinctiveness in connection with applicant’s identified carpet and rug services); Nextel Commc’ns, Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., 91 USPQ2d 1393, 1408 (TTAB 2009) (finding opposer’s contemporaneous use of the mark in connection with services closely related to applicant’s goods rose to the level necessary to rebut applicant’s contention of substantially exclusive use); Target Brands, Inc. v. Hughes, 85 USPQ2d 1676, 1682-83 (TTAB 2007) (finding substantial use of mark by opposer’s parent company and additional use of mark by numerous third parties "seriously undercuts if not nullifies applicant’s claim of acquired distinctiveness."); Marshall Field & Co. v. Mrs. Fields Cookies, 11 USPQ2d 1355, 1357-58 (TTAB 1989) ("[T]he existence of numerous third party users of a mark, even if junior, might well have a material impact on the Examiner’s decision to accept a party’s claim of distinctiveness."); Flowers Indus. Inc. v. Interstate Brands Corp., 5 USPQ2d 1580, 1588-89 (TTAB 1987) ("[L]ong and continuous use alone is insufficient to show secondary meaning where the use is not substantially exclusive.").

The use of the mark during the five years must also be continuous, without a period of "nonuse" or suspension of trade in the goods or services in connection with which the mark is used. 15 U.S.C. §1052(f); 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(2).

The substantially exclusive and continuous use must be "as a mark." 15 U.S.C. §1052(f); see In re Craigmyle, 224 USPQ 791, 793 (TTAB 1984) (finding registrability under §2(f) not established by sales over a long period of time where there was no evidence that the subject matter had been used as a mark); In re Kwik Lok Corp., 217 USPQ 1245, 1248 (TTAB 1983) (holding declarations as to sales volume and advertising expenditures insufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness. "The significant missing element in appellant’s case is evidence persuasive of the fact that the subject matter has been used as a mark.").

If the applicant chooses to seek registration under §2(f), 15 U.S.C. §1052(f), by using the statutory suggestion of five years of use as proof of distinctiveness, the applicant should submit a claim of distinctiveness. The following is the suggested format for a claim for a trademark or service mark, for a certification mark, for a collective membership mark, and for a collective trademark or collective service mark, based on 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(2), (b)(2), (c)(2), and (d)(2).

For a trademark or service mark, the claim of distinctiveness should read as follows, if accurate:

The mark has become distinctive of the goods/services through the applicant’s substantially exclusive and continuous use of the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress may lawfully regulate for at least the five years immediately before the date of this statement.

For a certification mark, the claim of distinctiveness should read as follows, if accurate:

The mark has become distinctive of the certified goods/services through the authorized users' substantially exclusive and continuous use of the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress may lawfully regulate for at least the five years immediately before the date of this statement.

For a collective membership mark, the claim of distinctiveness should read as follows, if accurate:

The mark has become distinctive of indicating membership in the collective membership organization through the members' substantially exclusive and continuous use of the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress may lawfully regulate for at least the five years immediately before the date of this statement.

For a collective trademark or collective service mark, the claim of distinctiveness should read as follows, if accurate:

The mark has become distinctive of the goods/services through the applicant's members' substantially exclusive and continuous use of the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress may lawfully regulate for at least the five years immediately before the date of this statement.

The claim of five years of use is required to be supported by a properly signed affidavit or declaration under 37 C.F.R. §2.20. See 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(2), (b)(2), (c)(2), (d)(2). The affidavit or declaration must be signed by a person properly authorized to sign on behalf of applicant under 37 C.F.R. §2.193(e)(1). See TMEP §611.03(a).

The following are guidelines regarding the form and language appropriate for a claim of five years of use:

Under Trademark Rule 2.41(a)(3), 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(3), an applicant may submit affidavits, declarations under 37 C.F.R. §2.20, depositions, or other appropriate evidence showing the duration, extent, and nature of the applicant’s use of a mark in commerce that may lawfully be regulated by the U.S. Congress, advertising expenditures in connection with such use, letters, or statements from the trade and/or public, or other appropriate evidence tending to show that the mark distinguishes the goods or services.

Establishing acquired distinctiveness by actual evidence was explained as follows in In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp.:

An evidentiary showing of secondary meaning, adequate to show that a mark has acquired distinctiveness indicating the origin of the goods, includes evidence of the trademark owner’s method of using the mark, supplemented by evidence of the effectiveness of such use to cause the purchasing public to identify the mark with the source of the product.

774 F.2d 1116, 1125, 227 USPQ 417, 422 (Fed. Cir. 1985). The kind and amount of evidence necessary to establish that a mark has acquired distinctiveness in relation to goods or services depends on the nature of the mark and the circumstances surrounding the use of the mark in each case. Yamaha Int’l Corp. v. Hoshino Gakki Co., 840 F.2d 1572, 1581, 6 USPQ2d 1001, 1008 (Fed. Cir. 1988); Roux Labs., Inc. v. Clairol Inc., 427 F.2d 823, 829, 166 USPQ 34, 39 (C.C.P.A. 1970) ; In re Hehr Mfg. Co., 279 F.2d 526, 528, 126 USPQ 381, 383 (C.C.P.A. 1960) ; In re Cap. Formation Couns., Inc., 219 USPQ 916, 918 (TTAB 1983) .

Evidence that only shows a mark used in conjunction with other wording may be insufficient to show that the mark has acquired distinctiveness. See In re Mogen David Wine Corp., 372 F.2d 539, 542, 152 USPQ 593, 595-96 (C.C.P.A. 1967) (holding evidence of a bottle design failed to prove secondary meaning where advertising depicting the bottle design always featured applicant’s word mark); In re Franklin Cnty. Hist. Soc’y, 104 USPQ2d 1085, 1093 (TTAB 2012) (noting none of applicant’s evidence showed use of the proposed mark "CENTER OF SCIENCE AND INDUSTRY" without the acronym "COSI," while other evidence only used the acronym to refer to applicant’s services).

The following sections provide examples of types of evidence that have been used, alone or in combination, to establish acquired distinctiveness. No single evidentiary factor is determinative. The value of a specific type of evidence and the amount necessary to establish acquired distinctiveness will vary according to the facts of the specific case. In addition, see TMEP §1212.01 regarding the factors considered when determining whether a mark has acquired distinctiveness.

Long-term use of the mark in commerce is one relevant factor to consider in determining whether a mark has acquired distinctiveness. See, e.g., In re La. Fish Fry Prods., Ltd., 797 F.3d 1332, 116 USPQ2d 1262 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (holding evidence of long use insufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness of FISH FRY PRODUCTS where evidence involved uses of LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS); In re Guaranteed Rate, Inc., 2020 USPQ2d 10869, at *6-7 (TTAB 2020) (finding §2(f) claim based on applicant’s use since 2000 not dispositive, even if the use was considered "substantially exclusive," due to the highly descriptive nature of applicant’s mark and the nature and number of third-party descriptive uses in the record); In re OEP Enters., Inc., 2019 USPQ2d 309323, at *22 (TTAB 2019) (finding applicant’s evidence of use since 1998 of an umbrella trade dress design "supports a finding of acquired distinctiveness to some extent because there is no evidence that competitive double canopy umbrellas had a mesh design between 1998 and 2017"); In re Hikari Sales USA, Inc., 2019 USPQ2d 111514, at *15 (TTAB 2019) (finding applicant’s evidence of continuous use of ALGAE WAFERS since at least Oct. 31, 1991 and advertisment of the goods sold under the mark since at least Oct. 1992 did not convince the Board that "ordinary purchasers of fish food have come to view that term primarily as an indicator of source"); In re Uncle Sam Chem. Co., 229 USPQ 233, 235 (TTAB 1986) (holding §2(f) claim of acquired distinctiveness persuasive where applicant had submitted declaration of its president supporting sales figures and attesting to over eighteen years of substantially exclusive and continuous use).

To support a §2(f) claim, use of the mark must be use in commerce, as defined in 15 U.S.C. §1127. See TMEP §§901–901.04 regarding what constitutes use in commerce.

Large-scale expenditures in promoting and advertising goods and services under a particular mark are significant to indicate the extent to which a mark has been used. However, proof of an expensive and successful advertising campaign is not in itself enough to prove secondary meaning. Mattel, Inc. v. Azrak-Hamway Int’l, Inc., 724 F.2d 357, 361 n.2, 221 USPQ 302, 305 n.2 (2d Cir. 1983) (citing Am. Footwear Corp. v. Gen. Footwear Co., 609 F.2d 655, 663, 204 USPQ 609, 615-16 (2d Cir. 1979)); see In re La. Fish Fry Prods., Ltd., 797 F.3d 1332, 116 USPQ2d 1262 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (finding evidence of sales and advertising expenditures insufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness of FISH FRY PRODUCTS where evidence involved uses of LOUISIANA FISH FRY PRODUCTS); In re Boston Beer Co. L.P., 198 F.3d 1370, 53 USPQ2d 1056 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (finding §2(f) claim based on annual sales under the mark of approximately eighty-five million dollars, and annual advertising expenditures in excess of ten million dollars – two million of which were spent on promotions and promotional items which included the phrase THE BEST BEER IN AMERICA – insufficient to establish distinctiveness, in view of the highly descriptive nature of the proposed mark).

The ultimate test in determining whether a designation has acquired distinctiveness is applicant’s success, rather than its efforts, in educating the public to associate the proposed mark with a single source. In re Sausser Summers, PC, 2021 USPQ2d 618, at *23 (TTAB 2021); Mini Melts, Inc. v. Reckitt Benckiser LLC, 118 USPQ2d 1464, 1480 (TTAB 2016) (citing In re Redken Labs., Inc., 170 USPQ 526, 529 (TTAB 1971)). The examining attorney must examine the advertising material to determine how the term is being used, the commercial impression created by such use, and what the use would mean to purchasers. In re Redken Labs., Inc., 170 USPQ at 528-29 (holding §2(f) evidence insufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness of THE SCIENTIFIC APPROACH for lectures concerning hair and skin treatment, notwithstanding ten years of use, over $500,000 in promotion and sponsorship expenses, and the staging of over 300 shows per year where advertising and promotional material showed only descriptive usage of applied-for mark); see In re Jasmin Larian, LLC, 2022 USPQ2d 290, at *42-44 (TTAB 2022) (finding no "look for" advertising in the record but rather applicant displayed its product design for handbags in advertising without any visible label or identifier, which caused some consumers to mistakenly associate the handbag with applicant's related business entity); In re Dimarzio, Inc., 2021 USPQ2d 1191, at *26-28 (TTAB 2021) (finding applicant's extensive advertising and promotional materials featuring prominent images of the applied-for color mark on the goods insufficient because the color was "not touted at all in [a]pplicant’s advertising," and was just one of many colors offered for applicant's goods, which strongly undercut applicant's claims "that the color cream [was] promoted as a mark and would be perceived as one by consumers"); In re OEP Enters., Inc., 2019 USPQ2d 309323, at *25 (TTAB 2019) (holding evidence of acquired distinctiveness deficient in part because "[a]pplicant’s consumer facing advertisements, like its ones to the trade, do little more than show the products, and they do not establish that consumers associate the features of the applied-for trade dress mark with [a]pplicant"); In re Chevron Intell. Prop. Grp. LLC, 96 USPQ2d 2026, 2031 (TTAB 2010) (finding evidence of acquired distinctiveness deficient in part because of the lack of advertisements promoting recognition of pole spanner design as a service mark); Mag Instrument Inc. v. Brinkmann Corp., 96 USPQ2d 1701, 1723 (TTAB 2010) (finding absence of "look for" advertisements damaging to attempt to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness of proposed configuration mark); Nextel Commc’ns, Inc. v. Motorola, Inc., 91 USPQ2d 1393, 1408 (TTAB 2009) (sustaining opposition on the ground that sound mark had not acquired distinctiveness in part because applicant failed to provide evidence corroborating that the mark was used in advertisements in such a way that it would be recognized as a source identifier for cellular telephones); In re ic! berlin brillen GmbH, 85 USPQ2d 2021, 2023 (TTAB 2008) (affirming refusal to register product configuration for spectacles and sunglasses, as the applicant failed to prove acquired distinctiveness chiefly because of the "absence of evidence of the advertising and/or promotion by the applicant of the earpiece design as a trademark"); In re E.I. Kane, Inc., 221 USPQ 1203, 1206 (TTAB 1984) (affirming refusal to register OFFICE MOVERS, INC., for moving services, notwithstanding §2(f) claim based on, inter alia, evidence of substantial advertising expenditures. "There is no evidence that any of the advertising activity was directed to creating secondary meaning in applicant’s highly descriptive trade name."); In re Kwik Lok Corp., 217 USPQ 1245, 1247-48 (TTAB 1983) (holding evidence insufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness for configuration of bag closures made of plastic, notwithstanding applicant’s statement that advertising of the closures involved several hundred thousands of dollars, where there was no evidence that the advertising had any impact on purchasers in perceiving the configuration as a mark); cf. In re Haggar Co., 217 USPQ 81, 84 (TTAB 1982) (holding background design of a black swatch registrable pursuant to §2(f) for clothing where applicant had submitted, inter alia, evidence of "very substantial advertising and sales," the Board finding the design to be, "because of its serrated left edge, something more than a common geometric shape or design").

If the applicant prefers not to specify the extent of its expenditures in promoting and advertising goods and services under the mark because this information is confidential, the applicant may indicate the types of media through which the goods and services have been advertised (e.g., national television) and how frequently the advertisements have appeared.