See TMEP §§1402.11–1402.11(k) regarding identifications of services, and TMEP §1401 regarding classification.

Section 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1127, defines "collective mark" as follows:

The term "collective mark" means a trademark or service mark--

Under the Trademark Act, a collective mark is owned by a collective entity even though the mark is used by the members of the collective.

There are basically two types of collective marks: (1) collective trademarks or collective service marks; and (2) collective membership marks. The distinction between these types of collective marks is explained in Aloe Creme Labs., Inc. v. Am. Soc'y for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Inc., 192 USPQ 170, 173 (TTAB 1976), as follows:

A collective trademark or collective service mark is a mark adopted by a "collective" (i.e., an association, union, cooperative, fraternal organization, or other organized collective group) for use only by its members, who in turn use the mark to identify their goods or services and distinguish them from those of nonmembers. The "collective" itself neither sells goods nor performs services under a collective trademark or collective service mark, but the collective may advertise or otherwise promote the goods or services sold or rendered by its members under the mark. A collective membership mark is a mark adopted for the purpose of indicating membership in an organized collective group, such as a union, an association, or other organization. Neither the collective nor its members uses the collective membership mark to identify and distinguish goods or services; rather, the sole function of such a mark is to indicate that the person displaying the mark is a member of the organized collective group.

See also In re Int'l Inst. of Valuers, 223 USPQ 350 (TTAB 1984) . See TMEP §1303 concerning collective trademarks and service marks; §1304.01 concerning collective membership marks; and §1305 concerning the distinction between collective trademarks or service marks from trademarks and service marks used by collective organizations.

Under the Trademark Act of 1905, registration could be based only on a person’s own use of a mark. The Act did not permit for registration of collective and certification marks because such marks are generally used by a member of a collective organization or an authorized user, while the owner of the mark exercises legitimate control over this use by others. However, the June 10, 1938 amendment to the Act of 1905, out of which §4 and the accompanying definitions in §45 grew, changed this limitation on use and provided for registration of a mark by an owner who "exercises legitimate control over the use of a collective mark." "Collective marks," however, were not defined in the federal statute until implementation of Section 45 of the Act of 1946.

Section 4 of the Trademark Act of 1946 provides the authority for the registration of collective and certification marks by persons exercising legitimate control over their use, even in the absence of an industrial or commercial establishment. 15 U.S.C. §1054. Section 45 defines collective marks and certification marks separately, as distinctly different types of marks. 15 U.S.C. §§1054, 1127. Additionally, the definition of collective mark in §45 encompasses collective trademarks and collective service marks, as well as collective membership marks, which indicate membership in a union, association, or other organization. 15 U.S.C. §1054. See TMEP §§1306.01–1306.01(b) regarding certification marks.

Although collective trademarks and collective service marks indicate the commercial origin of goods or services, they also indicate that the party providing the goods or services is a member of a certain group and meets the group's standards for admission. A collective mark is used by all members of the collective group; therefore, no one member can own the mark, and the collective organization holds the title to the collectively used mark for the benefit of all members of the group. In comparison, a trademark or service mark is used by the owner of the mark to indicate the commercial source or origin of the goods/services in the owner.

The collective organization itself neither sells the goods nor renders the services provided under the mark, but may advertise so as to publicize the mark and promote the goods or services sold by its members under the mark. For example, a collective organization of real-estate professionals does not render real-estate services, but rather promotes the real-estate services offered by its members. See Zimmerman v. Nat’l Assoc. of Realtors, 70 USPQ2d 1425, 1428 (TTAB 2004) .

Compared with a specimen for a trademark or service mark, which generally shows use of the mark by the owner, a specimen of use for a collective trademark or collective service mark must show use of the mark by a member of the collective organization. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(C); TMEP §1303.01(a)(i)(C). Such use must be on the member’s goods/packaging or in the sale, advertising, or rendering of the member’s services. See 37 C.F.R. §2.56(b)(3); TMEP §1303.01(a)(i)(C).

Under 37 C.F.R. §2.44, a complete application for a collective trademark or collective service mark must include the following:

37 C.F.R. §§2.44(a)(1), (a)(2)(i), (a)(3)(i), (a)(4), (a)(4)(B).

Requirements that differ in form from those in trademark or service mark applications. Most application requirements for collective trademarks and collective service marks are the same as those for regular trademarks and service marks. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(1). However, the filing basis and verification requirements for collective trademark and collective service mark applications differ in form from other trademark and service mark applications because of the difference between who owns and uses collective trademarks and collective service marks. See TMEP §§1303.01(a)–1303.01(a)(vi) for information regarding filing-basis requirements for collective trademarks and collective service marks and TMEP §§1303.01(b)–1301.01(b)(ii) for information regarding the verification of certain statements in collective trademark and collective service mark applications.

See TMEP Chapter 1600 for requirements post registration.

All applications for registration must include a filing basis, regardless of the type of mark, because this is the statutory basis for filing an application for registration of a mark in the United States. TMEP §806. There are five filing bases: (1) use of a mark in commerce under §1(a) of the Act; (2) bona fide intention to use a mark in commerce under §1(b) of the Act; (3) a claim of priority, based on an earlier-filed foreign application under §44(d) of the Act; (4) ownership of a registration of the mark in the applicant’s country of origin under §44(e) of the Act; and (5) extension of protection of an international registration to the United States under §66(a) of the Act. 15 U.S.C. §§1051(a)-(b), 1126(d)-(e), 1141f(a); 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4).

An applicant is not required to specify or otherwise satisfy the requirements for a filing basis to receive a filing date. See Kraft Grp. LLC v. Harpole, 90 USPQ2d 1837, 1840 (TTAB 2009) . If a §1 or §44 application does not specify a basis, the examining attorney must require in the first Office action that the applicant specify the basis for filing and submit all the elements required for that basis. If the applicant timely responds to the first Office action, but fails to specify a basis for filing, or fails to submit all the elements required for a particular basis, the examining attorney will issue a final Office action, if the application is otherwise in condition for final action.

In a §66(a) application, the basis for filing will have been established in the international registration on file at the IB.

See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4) and TMEP §1303.01(a)(i)-(a)(v) for a list of the requirements for each basis.

Under 15 U.S.C. §1051(a), §1054, and 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i), to establish a basis under §1(a) of the Trademark Act, the applicant must:

The Trademark Act defines "commerce" as commerce that may lawfully be regulated by the U.S. Congress, and "use in commerce" as the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade. 15 U.S.C. §1127; see TMEP §§901–901.04.

An applicant may claim both use in commerce under §1(a) of the Act and intent-to-use under §1(b) of the Act as a filing basis in the same application, but may not assert both §1(a) and §1(b) for the identical goods or services in the same application. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(c); see TMEP §806.02(b).

An applicant may not claim a §1(a) basis unless the mark was in use in commerce on or in connection with all the goods or services covered by the §1(a) basis as of the application filing date. Cf. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. Sunlyra Int’l, Inc., 35 USPQ2d 1787, 1791 (TTAB 1995) .

If the applicant claims use in commerce in addition to another filing basis, but does not specify which goods or services are covered by which basis, the USPTO may defer examination of the specimen(s) until the applicant identifies the goods or services for which use is claimed. TMEP §806.02(c).

In certain situations, notwithstanding the use of a collective trademark or collective service mark by the members of the collective, the collective itself may also use the same mark as a trademark or service mark for the goods or services covered by the collective trademark or collective service mark registration. See TMEP §1305. The "anti-use-by-owner rule" of §4 of the Trademark Act does not apply to collective marks. See 15 U.S.C. §1054. The Trademark Law Revision Act of 1988, which became effective on November 16, 1989, amended §4 to indicate that the "anti-use-by-owner rule" in that section applies only to certification marks. Cf. Roush Bakery Prods. Co. v. F.R. Lepage Bakery Inc., 4 USPQ2d 1401 (TTAB 1987) , aff’d, 851 F.2d 351, 7 USPQ2d 1395 (Fed. Cir. 1988), withdrawn, vacated and remanded, 863 F.2d 43, 9 USPQ2d 1335 (Fed. Cir. 1988), vacated and modified, 13 USPQ2d 1045 (TTAB 1989) (stating that the Board no longer believes that the anti-use-by-owner rule is applicable to trademarks).

The same mark may not be used both as a collective trademark or collective service mark and as a certification mark for the same goods or services. 37 C.F.R. §2.45(f); TMEP § 1306.04(f).

An applicant must specify the class of persons entitled to use the mark (i.e., the applicant’s members), indicating their relationship to the applicant, and the nature of the applicant’s control over the use of the mark. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(A). A statement that the applicant’s bylaws or other written provisions specify the manner of control is sufficient to satisfy this requirement. This statement does not have to be verified and, therefore, may be entered by examiner’s amendment.

The following language may be used for the above purpose:

Applicant controls the members’ use of the mark in the following manner: [specify, e.g., the applicant’s bylaws specify the manner of control].

When setting out the dates of use for a collective trademark on goods or collective service mark in connection with services, the applicant must state that the mark was first used by a member of the applicant rather than by the applicant. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(B).

The date of first use anywhere for a collective trademark application is the date when an applicant’s member’s goods were first sold or transported or, for a collective service mark application, when an applicant’s member’s services were first rendered, under the mark, if such use is bona fide and in the ordinary course of trade. See 15 U.S.C. §1127 (definition of "use" within the definition of "abandonment of mark"). For every applicant, whether foreign or domestic, the date of first use of a mark is the date of the first use anywhere, in the United States or elsewhere, regardless of whether the nature of the use was local or national, intrastate or interstate, or of another type.

The date of first use in commerce for a collective trademark application is the date when an applicant’s member’s goods were first sold or transported or, for a collective service mark application, when an applicant’s member’s services were first rendered, under the mark in a type of commerce that may be lawfully regulated by the U.S. Congress, if such use is bona fide and in the ordinary course of trade. See 15 U.S.C. §1127 (definition of "use" within the definition of "abandonment of mark"). See TMEP §901.01 for definitions of "commerce" and "use in commerce," and §901.03 regarding types of commerce.

In a §1(a) application, the applicant may not specify a date of use that is later than the filing date of the application. If an applicant who filed under §1(a) cannot show that a member used the mark in commerce on or before the application filing date, the applicant may amend the basis to §1(b). See 37 C.F.R. §2.35(b)(1). See TMEP §806.03 regarding amendments to the basis.

Neither a date of first use nor a date of first use in commerce is required to receive a filing date in an application based on use in commerce under §1(a) of the Act. If the application does not include a date of first use and/or a date of first use in commerce, the examining attorney must require that the applicant specify the date of first use and/or date of first use in commerce. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(B). The dates must be supported by an affidavit or declaration under 37 C.F.R. §2.20. See 37 C.F.R. §§2.44(a)(4)(i)(B), 2.71(c).

An applicant may not file an application on the basis of use of a mark in commerce if such use has been discontinued.

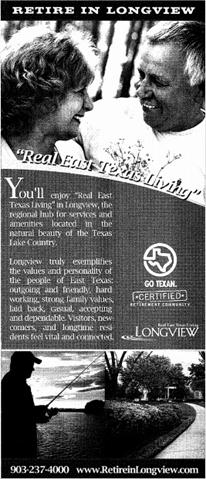

A specimen of use for a collective trademark or collective service mark must show how a member uses the mark on the member's goods or in the sale or advertising of the member’s services. 37 C.F.R. §2.56(b)(3).

The specimen must show use of the mark to indicate that the party providing the goods or services is a member of a certain group. For example, collective trademark specimens should show the mark used on the goods or packaging for the goods; collective service mark specimens should show the mark used in the sale or advertising of the services. See 37 C.F.R. §2.56(b)(3).

The purpose of the mark must be to indicate that the product or service is provided by a member of a collective group. However, the specimen itself does not have to state that purpose explicitly. The examining attorney should accept the specimen if the mark is used on the specimen to indicate the source of the product or service, and there is no information in the record that is inconsistent with the applicant's averments that the mark is a collective mark owned by a collective group and used by members of the group.

See TMEP §§904–904.07(b)(i) regarding specimens for trademarks and §§1301.04–1301.04(j) regarding specimens for service marks.

See TMEP §904.07(a) regarding whether a trademark or service mark specimen shows the mark as actually used in commerce.

In an application based on intent to use, the applicant must submit a verified statement that the applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce; that to the best of the signatory’s knowledge and belief, no other persons, except members, have the right to use the mark in commerce, either in the identical form or in such near resemblance as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods or services of such other persons, to cause confusion or mistake, or to deceive; and that the facts set forth in the application are true. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(ii); see 15 U.S.C. §§1051(b)(3)(B), 1054. See TMEP §1303.01(b)(i) for additional information regarding the requirements for the verified statement in applications under §1(b) of the Trademark Act.

Prior to registration, the applicant must file an allegation of use (i.e., either an amendment to allege use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(c) or a statement of use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(d), which states that (a) the mark is in use in commerce and (b) the applicant is exercising legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce, and includes dates of use, the filing fee for each class, and one specimen evidencing use of the mark for each class. See 37 C.F.R. §§2.76(b), 2.88(b). See 37 C.F.R. §2.76 and TMEP §§1104–1104.11 regarding amendments to allege use and 37 C.F.R. §2.88 and TMEP §§1109–1109.18 regarding statements of use.

Once an applicant claims a §1(b) basis for any or all the goods or services, the applicant may not amend the application to seek registration under §1(a) of the Act for those goods or services unless the applicant files an allegation of use under §1(c) or §1(d) of the Act. 37 C.F.R. §2.35(b)(8).

See TMEP Chapter 1100 for additional information about intent-to-use applications.

Section 44(d) of the Act provides a basis for receipt of a priority filing date, but not a basis for publication or registration. Before the application can be approved for publication, or for registration on the Supplemental Register, the applicant must establish a basis under §1(a), §1(b), or §44(e) of the Act. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(iv)(A); TMEP §1003.03. If the applicant claims a §1(b) basis, the applicant must file an allegation of use before the mark can be registered. See TMEP §1303.01(a)(ii) regarding the requirements for a §1(b) basis.

Under 15 U.S.C. §§1054, 1126(d), and 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(iv), the requirements for receipt of a priority filing date based on a previously filed foreign application are:

The scope of the goods/services covered by the §44 basis in the U.S. application may not exceed the scope of the goods/services in the foreign application or registration. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(2)(iii); TMEP §1402.01(b).

If an applicant properly claims a §44(d) basis in addition to another basis, the applicant may retain the priority filing date without perfecting the §44(e) basis. 37 C.F.R. §2.35(b)(3), (b)(4). See TMEP §806.04(b) regarding processing an amendment electing not to perfect a §44(e) basis and §806.02(f) regarding the examination of applications that claim §44(d) in addition to another basis. See TMEP §§1003–1003.08 for further information about §44(d) applications.

Under 15 U.S.C. §§1054, 1126(e), and 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(iii), the requirements for establishing a basis for registration under §44(e), relying on a registration granted by the applicant’s country of origin, are:

If the applicant does not submit a certification or a certified copy of the registration from its country of origin, the applicant must submit a true copy or photocopy of a document that has been issued to the applicant by, or certified by, the intellectual property office in the applicant’s country of origin. A photocopy of an entry in the intellectual property office’s gazette (or other official publication) or a printout from the intellectual property office’s website is not, by itself, sufficient to establish that the mark has been registered in that country and that the registration is in full force and effect. See TMEP §1004.01.

The scope of the goods/services covered by the §44 basis in the United States application may not exceed the scope of the goods/services in the foreign registration. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(2)(iii); TMEP §1402.01(b).

An application may be based on more than one foreign registration. If the applicant amends an application to rely on a different foreign registration, this is not considered a change in basis; however, the application must be republished. TMEP §1004.02. See TMEP §806.03 regarding amendments to add or substitute a basis.

See TMEP §§1004–1004.02 for further information about §44(e) applications.

A registration as a collective trademark or collective service mark in the United States may not be based on a foreign registration that is actually a trademark registration. See In re Löwenbräu München, 175 USPQ 178 (TTAB 1972) (noting that the U.S. registration cannot exceed the breadth or scope of the foreign registration on which it is based); TMEP §1402.01(b). The scope of the registration, i.e., the nature of the registration right, would not be the same.

The scope and nature of the registration is not always immediately apparent from a foreign registration certificate. Foreign registration certificates may not always clearly identify whether the mark is a trademark, service mark, collective mark, or certification mark and even when they indicate the type, the significance of the term used for the type is not always clear. For example, the designation "collective" represents a different concept in some foreign countries than it does in the United States. Moreover, while a certificate printed on a standardized form may be headed with the designation "trademark," the body of the certificate might contain language to the contrary.

If a foreign registration certificate has a heading that designates the mark as a collective trademark or collective service mark, or if the body of the foreign certificate contains language indicating that the registration is for a collective trademark or collective service mark, the foreign registration normally may be accepted to support registration in the United States as a collective trademark or collective service mark.

If a foreign registration certificate has a heading that designates the mark as a collective mark, or if the body of the foreign certificate contains language indicating that the registration is for a collective mark, this could indicate that the foreign registration is for a collective trademark, collective service mark, or collective membership mark. See TMEP §1302. In such a situation, the examining attorney must review the foreign registration to determine if there is a reference to goods or services such that the registration is for a collective trademark or collective service mark, or a reference indicating membership only such that the registration is for a collective membership mark. Id.

Whenever there is ambiguity about the scope or nature of the foreign registration, or whenever the examining attorney believes that the foreign certificate may not reflect the actual registration right, the examining attorney should inquire regarding the basis of the foreign registration, pursuant to 37 C.F.R §2.61.

Section 66(a) of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1141f(a), provides for a request for extension of protection of an international registration to the United States. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(v). The request must include a verified statement alleging that the applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress can regulate on or in connection with the goods or services specified in the international application/subsequent designation; that the signatory is properly authorized to execute the declaration on behalf of the applicant/holder; and that to the best of his/her knowledge and belief, no other person, firm, corporation, association, or other legal entity, except members, has the right to use the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress can regulate either in the identical form thereof or in such near resemblance thereto as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods or services of such other person, firm, corporation, association, or other legal entity, to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(v); see 15 U.S.C. §§1051(b)(3)(B), 1054. For a collective trademark or collective service mark application, the required verified statement is not part of the international registration on file at the International Bureau of the World Intellectual Property Organization ("IB"); therefore, the examining attorney must require the verified statement during examination. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

See TMEP § 1303.01(b)(ii) for additional information regarding the requirements for the verified statement in applications under §66(a) of the Trademark Act.

A §66(a) applicant may not change the basis or claim more than one basis unless the applicant meets the requirements for transformation under §70(c) of the Act. 37 C.F.R. §§2.35(a), 2.44(c). See TMEP §§1904.09–1904.09(b) regarding the limited circumstances under which a §66(a) application may be transformed into an application under §1 or §44.

Section 66(a) requires transmission of a request for extension of protection by the IB to the USPTO. Such basis may not be added or substituted as a basis in an application originally filed under §1 or §44.

Under 15 U.S.C. §1141g, Madrid Protocol Article 4(2), and 37 C.F.R. §7.27, the §66(a) applicant may claim a right of priority within the meaning of Article 4 of the Paris Convention if:

See Regs. Rule 9(4)(a)(iv).

The procedures for examining an application with multiple bases, amending or deleting a basis, and reviewing the basis information prior to publication or issuance of a registration are the same as for trademark and service mark applications. See TMEP §806.02 for information about multiple bases, §806.03 regarding amending the basis, §806.04 regarding deleting a basis, and §806.05 regarding review of a basis prior to publication or issue.

An application must include certain statements that are verified by the applicant or by someone who is authorized to verify facts on behalf of an applicant. See 15 U.S.C. §1051(a)(3), (b)(3); 37 C.F.R. §§2.44(a)(4)(i)(D), (a)(4)(ii), (a)(4)(iii)(B), (a)(4)(iv)(B), (a)(4)(v), 2.193(e)(1); TMEP §1303.01(b)(i) - (b)(ii).

In an application under §1 or §44 of the Trademark Act, a signed verification is not required for receipt of an application filing date under 37 C.F.R. §2.21(a). If the initial application does not include a proper verified statement, the examining attorney must require the applicant to submit a verified statement that relates back to the original filing date. See TMEP §§804.01–804.01(b) regarding the form of the oath or declaration, TMEP §1303.01(b)(i) regarding the essential allegations required to verify an application for registration of a mark, and TMEP §804.04 regarding persons properly authorized to sign a verification on behalf of an applicant.

In §66(a) applications, the verified statement is not part of the international registration on file at the IB; therefore the examining attorney must require the verified statement during examination. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(v), TMEP §§804.05, 1303.01(b)(ii), 1904.01(c).

The requirements for the verified statement in applications under §1 or §44 of the Trademark Act are set forth in 37 C.F.R. §§2.44(a)(4)(i)–(iv). See 15 U.S.C. §§1051(a)(3), 1051(b)(3), 1054, 1126. These allegations are required regardless of whether the verification is in the form of an oath ( TMEP §804.01(a)) or a declaration (TMEP §804.01(b)). See TMEP §1303.01(b)(ii) regarding the requirements for verification of a §66(a) application. See TMEP §§1303.01(a)–(a)(iv) for further information regarding filing-basis requirements, including the verified statement.

Truth of Facts Recited. Under 15 U.S.C. §§1051(a)(3)(B) and 1051(b)(3)(C), verification of an application for registration must include an allegation that "to the best of the verifier’s knowledge and belief, the facts recited in the application are accurate." The language in 37 C.F.R. §2.20 that "all statements made of [the signatory’s] own knowledge are true and all statements made on information and belief are believed to be true" satisfies this requirement. See 37 C.F.R. §§2.44(a)(4)(i)(D), (a)(4)(ii), (a)(4)(iii)(B), (a)(4)(iv)(B).

Use in Commerce and Exercising Legitimate Control. If the filing basis is §1(a), the applicant must submit a verified statement that the mark is in use in commerce and that the applicant is exercising legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(D). If this verified statement is not filed with the original application, it must also allege that, as of the application filing date, the mark was in use in commerce and the applicant was exercising legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

Bona Fide Intention and Entitlement to Exercise Legitimate Control. If the filing basis is §1(b), §44(d), or §44(e), the applicant must submit a verified statement that the applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce, and that to the best of the signatory’s knowledge and belief, no other persons, except members, have the right to use the mark in commerce, either in the identical form or in such near resemblance as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods or services of such other persons to cause confusion or mistake, or to deceive. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(ii), (a)(4)(iii)(B), (a)(4)(iv)(B). If this verified statement is not filed with the original application, it must also allege that, as of the application filing date, the applicant had a bona fide intention, and was entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

Ownership. In an application based on §1(a), the verified statement must allege that the applicant believes the applicant is the owner of the mark, and that to the best of the signatory’s knowledge and belief, no other persons, except members, have the right to use the mark in commerce, either in the identical form or in such near resemblance as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods or services of such other persons to cause confusion or mistake, or to deceive. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(D); see 15 U.S.C. §1051(a)(3)(A), (a)(3)(D).

Concurrent Use. The verification for concurrent use should be modified to indicate an exception that no other persons except members and the concurrent user(s) as specified in the application have the right to use the mark in commerce. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(d); see 15 U.S.C. §1051(a)(3)(D). See TMEP §1207.04(d)(ii) for concurrent use application requirements for a collective mark.

Affirmative, Unequivocal Averments Based on Personal Knowledge Required. The verification must include affirmative, unequivocal averments that meet the requirements of the Act and the rules. Statements such as "the undersigned [person signing the declaration] has been informed that the mark is in use in commerce [or has been informed that applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce] . . .," or wording that disavows the substance of the declaration, are unacceptable.

Verification Not Filed Within Reasonable Time. If the verified statement is not filed within a reasonable time after it is signed, the examining attorney will require the applicant to submit a substitute verified statement attesting that, as of the application filing date, the mark was in use in commerce and the applicant was exercising legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce (in an application based on §1(a)); or, as of the application filing date, the applicant had a bona fide intention, and was entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce (in an application based on §1(b) or §44). 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(1). See TMEP §804.03 for information regarding time between execution and filing of documents.

Substitute Verification. If the verified statement does not include all the necessary averments, the examining attorney will require a substitute or supplemental affidavit or declaration under 37 C.F.R. §2.20.

For a collective trademark or collective service mark in a §66(a) application, the verified statement is not part of the international registration on file at the IB; therefore, the examining attorney must require the verified statement during examination. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

Thus, in applications under §66(a) of the Act, the applicant must supplement the request for extension of protection to the United States to include a declaration that the applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress can regulate on or in connection with the goods or services specified in the international application/subsequent designation. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(v). The declaration must include a statement that the signatory is properly authorized to execute the declaration on behalf of the applicant and that to the best of his/her knowledge and belief, no other person, firm, corporation, association, or other legal entity, except members, has the right to use the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress can regulate, either in the identical form thereof or in such near resemblance thereto as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods/services of such other person, firm, corporation, association, or other legal entity, to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive. 37 C.F.R. 2. 44(a)(4)(v); see 15 U.S.C. §1141(f)(a).

Additionally, because the verified statement is not included with the initial application, the verified statement must also allege that, as of the application filing date, the applicant had a bona fide intention, and was entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

See TMEP § 1303.01(a)(v) for further information regarding filing basis requirements, including the verified statement.

The examination of applications to register collective trademarks and collective service marks is conducted in a manner similar to the examination of applications to register regular trademarks and service marks, using most of the same criteria of registrability. See 15 U.S.C. §1054. Thus, the same standards generally applicable to trademarks and service marks are used in considering issues such as descriptiveness, disclaimers, likelihood of confusion, and deceptiveness. However, use (specimens) and ownership requirements are slightly different due to the nature of collective marks. See TMEP §§1303.01(a)(i)–(a)(v). See TMEP §1303.01(a)(i)(C) regarding specimens for collective marks. See TMEP §1207.04 for information regarding a concurrent use registration.

Under the definition of "collective mark" in §45 of the Trademark Act, a collective mark must be owned by a collective entity. 15 U.S.C. §1127. The use of a collective trademark or collective service mark is by members of the collective, but no member may own the collective mark. That is, application may not be made by a mere member. Therefore, in an application based on use in commerce under §1(a) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1051(a), the applicant must assert that the applicant is exercising legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce.

Likelihood of confusion may arise from the contemporaneous use, by one party, of a collective trademark or collective service mark on the one hand and a trademark or service mark on the other. The same standards used to determine likelihood of confusion between trademarks and service marks also apply to collective marks. See 15 U.S.C. §1052(d); cf. In re Nat’l Novice Hockey League, Inc., 222 USPQ 638 (TTAB 1984); Allstate Life Ins. Co. v. Cuna Int’l, Inc., 169 USPQ 313 (TTAB 1971) , aff’d, 487 F.2d 1407, 180 USPQ 48 (C.C.P.A. 1973).

The finding of likelihood of confusion between a collective trademark or collective service mark and a trademark or service mark is not based on confusion as to the source of any goods or services provided by the members of the collective organization. Rather, the question is whether relevant persons are likely to believe that the trademark owner’s goods or services emanate from, are endorsed by, or are in some way associated with the collective organization. Cf. In re Code Consultants Inc., 60 USPQ2d 1699, 1701 (TTAB 2001).

The sole purpose of a collective membership mark is to indicate that the user of the mark is a member of a particular organization. See Constitution Party of Tex. v. Constitution Ass’n USA, 152 USPQ 443 (TTAB 1966) (holding cancellation of collective membership mark registration proper since mark was not being used to indicate membership in registrant).

Thus, membership marks are not trademarks or service marks in the ordinary sense; they are not used in business or trade, and they do not indicate commercial origin of goods or services. Registration of these marks fills the need of collective organizations who do not use the symbols of their organizations on goods or services but who still wish to protect their marks from use by others. See Ex parte Supreme Shrine of the Order of the White Shrine of Jerusalem, 109 USPQ 248 (Comm’r Pats. 1956), regarding the rationale for registration of collective membership marks.

A collective membership mark may comprise an individual letter or combination of letters, a single word or combination of words, a design alone, a name or nickname, or other matter that identifies the collective organization or indicates its purpose. A membership mark may, but need not, include the term "member" or the equivalent.

In addition to the mark being printed (the most common form), a membership mark may consist of an object, such as a flag, or may be a part of articles of jewelry, such as lapel pins or rings. See TMEP §1304.02(a)(i) and §1304.02(a)(i)(C) regarding use of membership marks and acceptable specimens.

Nothing in the Trademark Act prohibits the use of the same mark as a membership mark by members and, also, as a trademark or a service mark by the parent organization, but the same mark may not be used both as a membership mark and as a certification mark for the same goods or services. 37 C.F.R. §2.45(f); TMEP §1306.04(f).

See TMEP §1302.01 regarding the history of collective membership marks.

Under 37 C.F.R. §2.44, a complete application for a collective membership mark must include the following:

37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(1), (a)(2)(ii), (a)(3)(ii), (a)(4).

Requirements that differ in form from those in trademark or service mark applications. Most application requirements for collective membership marks are the same as those for regular trademarks and service marks. However, the filing basis, verification, identification, and classification requirements for collective membership mark applications differ in form from other trademark and service mark applications because of the difference between who owns and uses collective membership marks. See TMEP §§1304.02(a)-(a)(v) for information regarding filing basis requirements, §§1304.02(b)-(b)(ii) for information regarding the verification of certain statements, §1304.02(c) for identification requirements, and §1304.02(d) for classification requirements in collective membership mark applications.

See TMEP Chapter 1600 for post-registration requirements.

See TMEP §1303.01(a) for information regarding an application filing basis for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to collective membership marks.

For a list of the requirements pertaining to each filing basis, see 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4) and TMEP §§1304.02(a)(i)–(v).

Registration of a collective membership mark under §1(a) is based on actual use of the mark by the members of a collective organization. The owner of the mark exercises control over the use of the mark; however, because the sole purpose of a membership mark is to indicate membership, use of the mark is by its members. See In re Triangle Club of Princeton Univ., 138 USPQ 332 (TTAB 1963) (collective membership mark registration denied because specimen did not show use of mark by members).

Under 15 U.S.C. §1051(a), §1054, and 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i), to establish a basis under §1(a) of the Trademark Act, the applicant must:

The Trademark Act defines "commerce" as commerce that may lawfully be regulated by the U.S. Congress, and "use in commerce" as the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade. 15 U.S.C. §1127; see TMEP §§901–901.04.

An applicant may not assert both §1(a) and §1(b) for the same collective membership organization in the same application. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(c); see TMEP §806.02(b).

Nothing in the Trademark Act prohibits the use of the same mark as a collective membership mark by members and, also, as a trademark or service mark by the parent organization (see TMEP §1303.01), but the same mark may not be used both as a collective membership mark and as a certification mark for the same goods or services. 37 C.F.R. §2.45(f); TMEP §1306.04(f).

See TMEP § 1303.01(a)(i)(A) for information regarding the requirement for a Manner/Method of Control statement for a collective trademark or collective service mark. This requirement applies similarly to collective membership marks.

When setting out dates of use of a collective membership mark, the applicant must state that the mark was first used by a member of the applicant rather than by the applicant, and that the mark was first used on a specified date to indicate membership rather than first used on goods or in connection with services.

The date of first use anywhere is the date when an applicant’s member first indicates membership in the collective organization under the mark, if such use is bona fide and in the ordinary course of trade. See 15 U.S.C. §1127 (definition of "use" within the definition of "abandonment of mark"). For every applicant, whether foreign or domestic, the date of first use of a mark is the date of the first use anywhere, in the United States or elsewhere, regardless of whether the nature of the use was local or national, intrastate or interstate, or of another type.

The date of first use in commerce is the date when an applicant’s member first indicates membership in the collective organization under the mark in a type of commerce that may be lawfully regulated by the U.S. Congress, if such use is bona fide and in the ordinary course of trade. See 15 U.S.C. §1127 (definition of "use" within the definition of "abandonment of mark"). See TMEP §901.01 for definitions of "commerce" and "use in commerce," and §901.03 regarding types of commerce.

In a §1(a) application, the applicant may not specify a date of use that is later than the filing date of the application. If an applicant who filed under §1(a) cannot show that a member used the mark in commerce on or before the application filing date, the applicant may amend the basis to §1(b). See 37 C.F.R. §2.35(b)(1). See TMEP §806.03 regarding amendments to the basis.

Neither a date of first use nor a date of first use in commerce is required to receive a filing date in an application based on use in commerce under §1(a) of the Act. If the application does not include a date of first use and/or a date of first use in commerce, the examining attorney must require that the applicant specify the date of first use and/or date of first use in commerce. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(B). The dates must be supported by an affidavit or declaration under 37 C.F.R. §2.20. See 37 C.F.R. §§2.44(a)(4)(i)(B), 2.71(c).

An applicant may not file an application on the basis of use of a mark in commerce if such use has been discontinued.

The owner of a collective membership mark exercises control over the use of the mark but does not itself use the mark to indicate membership. Therefore, a proper specimen of use of a collective membership mark must show use by members to indicate membership in the collective organization. 37 C.F.R. §2.56(b)(4); In re Int’l Ass’n for Enterostomal Therapy, Inc., 218 USPQ 343 (TTAB 1983) ; In re Triangle Club of Princeton Univ., 138 USPQ 332 (TTAB 1963).

The most common types of specimens are membership cards and certificates. The applicant may submit as a specimen a blank or voided membership card or certificate.

For trade or professional associations, decals bearing the mark for use by members on doors or windows in their establishments, wall plaques bearing the mark, or decals or plates for use, e.g., on members’ vehicles, are satisfactory specimens. If the members are in business and place the mark on their business stationery to show their membership, pieces of such stationery are acceptable. Flags, pennants, and banners of various types used in connection with political parties, club groups, or the like could be satisfactory specimens.

Many associations, particularly fraternal societies, use jewelry such as pins, rings, or charms to indicate membership. See In re Triangle Club of Princeton Univ., supra. However, not every ornamental design on jewelry is necessarily an indication of membership. The record must show that the design on a piece of jewelry is actually an indication of membership before the jewelry can be accepted as a specimen of use. See In re Inst. for Certification of Computer Prof’ls, 219 USPQ 372 (TTAB 1983) (in view of contradictory evidence in record, specimen with nothing more than CCP thereon was not considered evidence of membership); In re Mountain Fuel Supply Co., 154 USPQ 384 (TTAB 1967) (design on specimen did not indicate membership in organization, but merely showed length of service).

Shoulder, sleeve, pocket, or similar patches, or lapel pins, whose design constitutes a membership mark and which are authorized by the parent organization for use by members on garments to indicate membership, are normally acceptable as specimens. Clothing authorized by the parent organization to be worn by members may also be an acceptable specimen.

A specimen that shows use of the mark by the collective organization itself, rather than by a member, is not acceptable. Collective organizations often publish various kinds of printed material, such as catalogs, directories, bulletins, newsletters, magazines, programs, and the like. Placement of the mark on these items by the collective organization represents use of the mark as a trademark or service mark to indicate that the collective organization is the source of the material. The mark is not placed on these items by the parent organization to indicate membership of a person in the organization.

See TMEP §904.07(a) regarding whether a trademark or service mark specimen shows the mark used in commerce.

See TMEP §1304.03(b) regarding specimen refusals specific to collective membership marks.

See TMEP §1303.01(a)(ii) for information regarding an intent-to-use filing basis for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to collective membership marks, with the only difference being that the verified statement refers to a collective membership organization rather than goods or services.

See TMEP §1303.01(a)(iii) for information regarding a §44(d) filing basis for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to collective membership marks, with the only difference being that the verified statement refers to a collective membership organization rather than goods or services.

See TMEP §1303.01(a)(iv) for information regarding a §44(e) filing basis for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to collective membership marks, with only two differences. First, the verified statement refers to a collective membership organization rather than goods or services. Second, the scope of the nature of the collective membership organization covered by the §44 basis in the U.S. application may not exceed the scope of the nature of the collective membership organization identified in the foreign application or registration. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(2)(iii); TMEP §1402.01(b).

See TMEP §1303.01(a)(iv)(A) for information regarding the scope of a foreign registration for a collective trademark or collective service mark. This information applies similarly to collective membership marks.

See TMEP §1303.01(a)(v) for information regarding a §66(a) filing basis for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to collective membership marks, with the only difference being that the verified statement refers to a collective membership organization rather than goods or services.

The procedures for examining an application with multiple bases, amending or deleting a basis, and reviewing the basis information prior to publication or issuance of a registration are the same as for trademark and service mark applications. See TMEP §806.02 for information about multiple bases, §806.03 regarding amending the basis, §806.04 regarding deleting a basis, and §806.05 regarding review of a basis prior to publication or issue.

See TMEP §1303.01(b) for information about the verification of certain statements for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to collective membership marks, except for the statement regarding the applicant’s bona fide intent and entitlement to exercise legitimate control and the applicant’s ownership statement.

See TMEP §1303.01(b)(i) for information about the requirements for the verified statement in applications under §1 or §44 for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to collective membership marks. The two exceptions are the following requirements, which differ only in form.

Bona Fide Intention and Entitlement to Exercise Legitimate Control. If the filing basis is §1(b), §44(d), or §44(e), the applicant must submit a verified statement that the applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce, and that to the best of the signatory’s knowledge and belief, no other persons, except members, have the right to use the mark in commerce, either in the identical form or in such near resemblance as to be likely, when used in connection with the collective membership organization of such other persons, to cause confusion or mistake, or to deceive. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(ii), (a)(4)(iii)(B), (a)(4)(iv)(B). If this verified statement is not filed with the original application, it must also allege that, as of the application filing date, the applicant had a bona fide intention, and was entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

Ownership. In an application based on §1(a), the verified statement must allege that the applicant believes the applicant is the owner of the mark, and that to the best of the signatory’s knowledge and belief, no other persons, except members, have the right to use the mark in commerce, either in the identical form or in such near resemblance as to be likely, when used in connection with the collective membership organization of such other persons, to cause confusion or mistake, or to deceive. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(D); see 15 U.S.C. §§1051(a)(3)(A), 1051(a)(3)(D).

See TMEP §§1304.02(a) - (a)(iv) for further information regarding filing-basis requirements, including the verified statement.

For a collective membership mark in a §66(a) application, the verified statement is not part of the international registration on file at the IB; therefore, the examining attorney must require the verified statement during examination. See 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

In applications under §66(a) of the Act, the applicant must supplement the request for extension of protection to the United States to include a declaration that the applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress can regulate to indicate membership in the collective organization. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(v). The declaration must include a statement that the signatory is properly authorized to execute the declaration on behalf of the applicant and that to the best of his/her knowledge and belief, no other person, firm, corporation, association, or other legal entity, except members, has the right to use the mark in commerce that the U.S. Congress can regulate either in the identical form thereof or in such near resemblance thereto as to be likely, when used in connection with the collective membership organization of such other person, firm, association, or other legal entity, to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive. 37 C.F.R. 2. 44(a)(4)(v); see 15 U.S.C. §1141(f)(a).

Additionally, because the verified statement is not included with the initial application, the verified statement must also allege that, as of the application filing date, the applicant had a bona fide intention, and was entitled, to exercise legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(b)(2).

See TMEP § 1303.01(a)(v) for further information regarding filing-basis requirements, including the verified statement.

The purpose of a collective membership mark is to indicate membership in an organization; therefore, an identification of goods or services would not be appropriate in connection with a collective membership mark. More accurate identification language would be "indicating membership in an organization (association, club, or the like) . . .," followed by a phrase indicating the nature of the organization or association, for example, "indicating membership in an organization of computer professionals" or "indicating membership in a motorcycle club."

The nature of an organization can be indicated by specifying the area of activity of its members (e.g., they may sell lumber, cosmetics, or food, or may deal in chemical products or household goods, or provide services as fashion designers, engineers, or accountants). If goods or services are not directly involved, the nature of an organization can be indicated by specifying the organization’s type or purpose (such as a service or social club, a political society, a trade association, a beneficial fraternal organization, or the like). Detailed descriptions of an organization’s objectives or activities are not necessary. It is sufficient if the identification indicates broadly either the field of activity as related to the goods or services, or the general type or purpose of the organization.

Section 1 and §44 Applications. In applications under §1 or §44 of the Trademark Act, collective membership marks are classified in U.S. Class 200. 37 C.F.R. §6.4. U.S. Class 200 was established as a result of the decision in Ex parte Supreme Shrine of the Order of the White Shrine of Jerusalem, 109 USPQ 248 (Comm’r Pats. 1956). Before this decision, there was no registration of membership insignia on the theory that all collective marks were either collective trademarks or collective service marks. Some marks that were actually membership marks were registered under the Trademark Act of 1946 as collective service marks, and a few were registered as collective trademarks. That practice was discontinued upon the clarification of the basis for registration of membership marks and the creation of U.S. Class 200.

Section 66(a) Applications. A §66(a) application may indicate that the mark is a "Collective, Certificate or Guarantee Mark" or the identification may indicate that the mark is intended to indicate membership. In such cases, the examining attorney will require the applicant to clarify for the record the type of mark for which it seeks protection. The examining attorney must also require the applicant to comply with the requirements for the particular type of mark, i.e., collective trademark, collective service mark, collective membership mark, or certification mark. See TMEP §§1303–1303.02(b) regarding collective trademarks and collective service marks, §§1304–1304.03(c) regarding collective membership marks, and §§1306–1306.06(c) regarding certification marks.

If a §66(a) applicant indicates that the mark is a collective membership mark, the USPTO will not reclassify it into U.S. Class 200 because the classification of such applications may not be changed from that assigned by the International Bureau of the World Intellectual Property Organization (IB). TMEP §§1401.03(d), 1904.02(b). However, the examining attorney must ensure that the applicant complies with all other U.S. requirements for collective membership marks. See TMEP §§1304–1304.03(c).

An application to register a collective membership mark on the Principal Register must meet all the criteria for registration of other marks on the Principal Register. 15 U.S.C. §1054; see 37 C.F.R. §2.46. Likewise, when determining the registrability of a collective membership mark on the Supplemental Register, the same standards are used as are applied to other types of marks. See 37 C.F.R. §2.47.

The examination of collective membership mark applications is conducted in the same manner as the examination of applications to register trademarks and service marks, using the same criteria of registrability. Thus, the same standards generally applicable to trademarks and service marks are used in considering issues such as descriptiveness or disclaimers. See Racine Indus. Inc. v. Bane-Clene Corp., 35 USPQ2d 1832, 1837 (TTAB 1994) ; In re Ass’n of Energy Eng’rs, Inc., 227 USPQ 76, 77 (TTAB 1985) ; In re Int’l Ass’n for Enterostomal Therapy, Inc., 218 USPQ 343 (TTAB 1983) . However, use (specimens) and ownership requirements are slightly different due to the nature of collective membership marks indicating membership rather than commercial origin.

See TMEP §1207.04 for information regarding seeking a concurrent use registration.

Under the definition of "collective mark" in §45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1127, only a "cooperative, an association or other collective group or organization" can become the owner of a collective mark. However, there is great variety in the organizational form of collective groups whose members use membership marks. The terms "group" and "organization" are broad enough to cover all groups of persons who are brought together in an organized manner such as to justify their being called "collective."

The organization is usually an association, either incorporated or unincorporated, but is not limited to being an association and may have some other form.

A collective membership mark may be owned by someone other than the collective organization whose members use the mark, and the owner might not itself be a collective organization. An example is a business corporation who forms a club for persons meeting certain qualifications, and arranges to retain control of the group and of the mark used by the members of the group. The corporation that has retained control over the use of the mark is the owner of the mark, and is entitled to apply to register the mark. In re Stencel Aero Eng’g Corp., 170 USPQ 292 (TTAB 1971) .

To apply to register a collective membership mark, the collective organization which owns the mark must be a person capable of suing and being sued in a court of law. See 15 U.S.C. §1127; TMEP §803.01. The persons who compose a collective group may be either natural or juristic persons.

Application to register a membership mark must be made by the organization or person (including juristic persons) that controls or intends to control the use of the mark by the members and, therefore, owns or is entitled to use the mark. See 15 U.S.C. §1054; In re Stencel Aero Eng’g Corp., 170 USPQ 292 (TTAB 1971) . Application may not be made by a mere member.

Whether matter functions as a collective membership mark is determined by the specimen and evidence of record. It is the use of the mark to indicate membership, rather than the character of the matter composing the mark, that determines whether a term or other designation is a collective membership mark. See Ex parte Grand Chapter of Phi Sigma Kappa, 118 USPQ 467 (Comm’r Pats. 1958) (holding that use of Greek letter abbreviations on athletic jerseys did not function as collective membership marks indicating membership in Greek letter societies); In re Mountain Fuel Supply Co., 154 USPQ 384 (TTAB 1967) (holding that the design on a jewelry pin merely indicated longevity of service rather than membership in a collective organization). If a proposed mark does not function as a mark indicating membership, the examining attorney must refuse registration under §§1, 2, 4, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1054, 1127. See TMEP §1304.03(b)(ii) regarding specimens showing use as degrees or titles. See TMEP §904.07(b) for information about matter that fails to function as a trademark or service mark.

Professional, technical, educational, and similar organizations often adopt letters or similar designations to be used by persons to indicate that the persons have passed certain tests or completed certain courses of instruction that are specified by the organization, or have demonstrated a degree of proficiency to the satisfaction of the organization. When such a symbol is used solely as a personal title or degree for an individual (i.e., it is used in a manner that identifies only a title or degree conferred on this individual), then it does not serve to indicate membership in an organization, and registration as a membership mark must be refused. In re Int’l Inst. of Valuers, 223 USPQ 350 (TTAB 1984) (registration properly refused where use of the mark on specimen indicated award of a degree or title, and not membership in collective organization); see also In re Nat’l Soc’y of Cardiopulmonary Technologists, Inc., 173 USPQ 511 (TTAB 1972) ; cf. In re Thacker, 228 USPQ 961 (TTAB 1986); In re Nat’l Ass’n of Purchasing Mgmt., 228 USPQ 768 (TTAB 1986) ; In re Mortg. Bankers Ass’n of Am., 226 USPQ 954 (TTAB 1985) .

If the proposed mark functions merely as a degree or title, the examining attorney must refuse registration under §§1, 2, 4, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051, 1052, 1054, 1127, on the ground that the matter does not function as a collective membership mark. See TMEP §1304.03(b)(i).

Likelihood of confusion may arise from the contemporaneous use, by one party, of a collective membership mark on the one hand and a trademark or service mark on the other. The same standards used to determine likelihood of confusion between trademarks and service marks also apply to collective membership marks. See 15 U.S.C. §1052(d); In re Nat’l Novice Hockey League, Inc., 222 USPQ 638 (TTAB 1984) ; Allstate Life Ins. Co. v. Cuna Int’l, Inc., 169 USPQ 313 (TTAB 1971) , aff’d, 487 F.2d 1407, 180 USPQ 48 (C.C.P.A. 1973).

The finding of likelihood of confusion between a collective membership mark and a trademark or service mark is not based on confusion as to the source of any goods or services provided by the members of the collective organization. Rather, the question is whether relevant persons are likely to believe that "the trademark owner’s goods or services emanate from or are endorsed by or are in some other way associated with the collective organization." Pierce-Arrow Soc’y v. Spintek Filtration, Inc., 2019 USPQ2d 471774, at *8-9 (TTAB 2019) (quoting Carefirst of Md., Inc. v. FirstHealth of the Carolinas Inc., 77 USPQ2d 1492, 1513 (TTAB 2005)); In re Code Consultants Inc., 60 USPQ2d 1699, 1701 (TTAB 2001) . For purposes of Section 2(d), the identification of goods or services is used to determine the relevant consuming public. Pierce-Arrow Soc’y, 2019 USPQ2d 471774, at *9 (citing In re Gulf Coast Nutritionals, Inc., 106 USPQ2d 1243, 1247 (TTAB 2013)). Relevant purchasers for a collective membership mark consist of "those persons or groups of persons for whose benefit the membership mark is displayed." Id. (citing Carefirst of Md., Inc., 77 USPQ2d at 1513).

A collective organization may itself use trademarks and service marks to identify its goods and services, as opposed to collective trademarks and service marks or collective membership marks used by the collective’s members. See B.F. Goodrich Co. v. Nat'l Coops., Inc., 114 USPQ 406 (Comm’r Pats. 1957) (mark used to identify tires made for applicant cooperative and sold by its distributors is a trademark, not a collective mark that identifies goods of applicant’s associated organizations; applicant alone provides specifications and other instructions and applicant alone is responsible for faulty tires).

The examination of applications to register trademarks and service marks used or intended to be used by collective organizations is conducted in the same manner as for other trademarks and service marks, using the same criteria of registrability.

The form of the application used by collective organizations is the same as for those used or intended to be used by other applicants. The collective organization should be listed as the applicant, because it uses or intends to use the mark itself. The specimen submitted must be material applied by the collective organization to its goods or used in connection with its services.

Section 4 of the Trademark Act, provides for the registration of "certification marks, including indications of regional origin," which are defined in Section 45 as follows:

The term "certification mark" means any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof--

to certify regional or other origin, material, mode of manufacture, quality, accuracy, or other characteristics of such person’s goods or services or that the work or labor on the goods or services was performed by members of a union or other organization.

Based on the statute, there are generally three types of certification marks, that is, those that certify:

Differences between certification marks and trademarks or service marks. Two characteristics differentiate certification marks from trademarks or service marks: first, a certification mark is not used by its owner but rather by authorized users and, second, a certification mark does not indicate commercial source or distinguish the goods or services of one person from those of another person but rather indicates that the goods/services of authorized users are certified as to a particular aspect of the goods/services. See TMEP §1306.06(a) for a discussion of the distinction between a certification mark and a collective trademark, collective service mark, or collective membership mark.

A certification mark may not be used, in the trademark sense of "used," by the owner of the mark; it may be used only by a person or persons other than the owner of the mark. That is, the owner of a certification mark does not apply the mark to his or her goods or services and, in fact, usually does not attach or apply the mark at all. The mark is generally applied by other persons to their goods or services, with authorization from the owner of the mark.

The owner of a certification mark does not produce the goods or perform the services in connection with which the mark is used, and thus does not control their nature and quality. Therefore, it is not appropriate to inquire about control over the nature and quality of the goods or services. What the owner of the certification mark does control is use of the mark by others on their goods or services. This control consists of taking steps to ensure that the mark is applied only to goods or services that contain the characteristics or meet the requirements that the certifier/owner has established or adopted for the certification. See TMEP §1306.03(b) regarding submission of the standards established by the certifier to determine whether the certification mark may be used in relation to the goods and/or services of others.

A certification mark "is a special creature created for a purpose uniquely different from that of an ordinary service mark or trademark . . . ." In re Fla. Citrus Comm’n, 160 USPQ 495, 499 (TTAB 1968). That is, the purpose of a certification mark is to inform purchasers that the goods or services of a person possess certain characteristics or meet certain qualifications or standards established by another person. A certification mark does not indicate origin in a single commercial or proprietary source the way a trademark or service mark does. Rather, the same certification mark is used on the goods or services of many different producers.

The message conveyed by a certification mark is that the goods or services have been examined, tested, inspected, or in some way checked by a person who is not their producer, using methods determined by the certifier/owner. The placing of the mark on goods, or its use in connection with services, thus constitutes a certification by someone other than the producer that the prescribed characteristics or qualifications of the certifier for those goods or services have been met.

If the applicant has used the appropriate application form, the application will clearly indicate that the mark is intended to be a certification mark and should include the required elements. For certification mark applications based on §66(a) of the Trademark Act, the request for extension of protection will include a field indicating that the mark is a "Collective, Certificate or Guarantee Mark." See TMEP §1904.02(d) regarding requirements for §66(a) applications for certification and collective marks.

The examining attorney may also determine that the mark is a certification mark based on a review of the information in the application, which should include a certification statement or language indicating the mark’s use, or intended use, to certify some aspect of the goods or services, such as certifying regional origin, or that the labor was performed by a certain group, or that the goods or services meet certain safety standards. If the nature of the mark and its intended use are unclear, the examining attorney must seek clarification, through a Trademark Rule 2.61(b) requirement for additional information or, if appropriate, by telephone or email communication. See 37 C.F.R. §2.61(b); TMEP §§1306.04(b)(ii), TMEP §1306.06-1306.06(b). Any clarification regarding the certification statement that is received by informal communication must be recorded in a Note to the File. In addition, if certain required elements, such as those discussed in TMEP §1306.03, are missing or unacceptable, the applicant will be required to provide or amend them.

Under 37 C.F.R. §2.45, a complete application for a certification mark must include the following:

Requirements that differ in form from those in trademark or service mark applications. Most application requirements for certification marks are the same as those for regular trademarks and service marks. However, the filing basis, verification, identification, and classification requirements for certification mark applications differ in form from other trademarks and service mark applications because of the difference between who owns and uses certification marks. See TMEP §1306.02(a)-(a)(v) for information regarding filing-basis requirements, §§1306.02(b)-(b)(ii) for information regarding the verification of certain statements, §1306.02(c) for identification requirements, and §1306.02(d) for classification requirements in certification mark applications.

See TMEP §1306.03 for further information regarding the special elements of certification mark applications. See TMEP Chapter 1600 for post-registration requirements.

See TMEP §1303.01(a) for information regarding an application filing basis for a collective trademark or collective service mark. These requirements apply similarly to certification marks.

For a list of the requirements pertaining to each filing basis, see 37 C.F.R. §2.45(a)(4)(i)-(v) and TMEP §§1306.02(a)(i)-(v).

Under 15 U.S.C. §1051(a), §1054, and 37 C.F.R. §2.45(a)(4)(i), to establish a basis under §1(a) of the Trademark Act, the applicant must:

The Trademark Act defines "commerce" as commerce which may lawfully be regulated by the U.S. Congress, and "use in commerce" as the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade. 15 U.S.C. §1127; see TMEP §§901–901.04.

An applicant may claim both use in commerce under §1(a) of the Act and intent to use under §1(b) of the Act as a filing basis in the same application, but may not assert both §1(a) and §1(b) for the identical goods or services in the same application. 37 C.F.R. §2.45(c); see TMEP §806.02(b).

An applicant may not claim a §1(a) basis unless the mark was in use in commerce on or in connection with all the goods or services covered by the §1(a) basis as of the application filing date. Cf. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. Sunlyra Int’l, Inc., 35 USPQ2d 1787, 1791 (TTAB 1995) .

If the applicant claims use in commerce in addition to another filing basis, but does not specify which goods or services are covered by which basis, the USPTO may defer examination of the specimen(s) until the applicant identifies the goods or services for which use is claimed. TMEP §806.02(c).

See TMEP §1306.03(a) regarding statements specifying what the mark certifies, §1306.03(b) regarding certification standards, and §1306.03(c) regarding a statement that the applicant is not engaged in the production or marketing of the goods/services.

When specifying the dates of use as a certification mark, the applicant must indicate that the certification mark was first used by the applicant’s authorized users because a certification mark is not used by the applicant itself. See 37 C.F.R. §2.45(a)(4)(i)(D).

The date of first use anywhere is the date when an applicant’s authorized user’s goods were first sold or transported, or an applicant’s authorized user’s services were first rendered, under the mark, if such use is bona fide and in the ordinary course of trade. See 15 U.S.C. §1127 (definition of "use" within the definition of "abandonment of mark"). For every applicant, whether foreign or domestic, the date of first use of a mark is the date of the first use anywhere, in the United States or elsewhere, regardless of whether the nature of the use was local or national, intrastate or interstate, or of another type.

The date of first use in commerce is the date when an applicant’s authorized user’s goods were first sold or transported, or an applicant’s authorized user’s services were first rendered, under the mark in a type of commerce that may be lawfully regulated by the U.S. Congress, if such use is bona fide and in the ordinary course of trade. See 15 U.S.C. §1127 (definition of "use" within the definition of "abandonment of mark"). See TMEP §901.01 for definitions of "commerce" and "use in commerce," and §901.03 regarding types of commerce.

In a §1(a) application, the applicant may not specify a date of use that is later than the filing date of the application. If an applicant who filed under §1(a) cannot show that an authorized user used the mark in commerce on or before the application filing date, the applicant may amend the basis to §1(b). See 37 C.F.R. §2.35(b)(1). See TMEP §806.03 regarding amendments to the basis.

Neither a date of first use nor a date of first use in commerce is required to receive a filing date in an application based on use in commerce under §1(a) of the Act. If the application does not include a date of first use and/or a date of first use in commerce, the examining attorney must require that the applicant specify the date of first use and/or date of first use in commerce. See 37 C.F.R. §2.45(a)(4)(i)(D). The dates must be supported by an affidavit or declaration under 37 C.F.R. §2.20. See 37 C.F.R. §§2.45(a)(4)(i)(D), 2.71(c).

An applicant may not file an application on the basis of use of a mark in commerce if such use has been discontinued.

A certification mark specimen must show how a person other than the owner uses the mark to reflect certification of regional or other origin, material, mode of manufacture, quality, accuracy, or other characteristics of that person’s goods or services; or that members of a union or other organization performed the work or labor on the goods or services. 37 C.F.R. §2.56(b)(5); see In re Council on Certification of Nurse Anesthetists, 85 USPQ2d 1403 (TTAB 2007) .

Although a certification mark performs a different function from a trademark or a service mark, users of certification marks typically apply them to goods and services in a manner similar to trademarks and service marks. That is, certification marks appear on labels, tags, or packaging for goods, or on materials used in the sale or advertising of services. Thus, specimens of use in certification mark applications generally are examined using the same standards that apply to specimens for trademarks and service marks. See TMEP §§904–904.07(b)(i) regarding specimens for trademarks and TMEP §1301.04-TMEP §1301.04(j) regarding specimens for service marks. However, because it is improper for certification marks to be used by their owners, any specimen of use submitted in support of a certification mark application must show use of the mark as a certification mark by an authorized user. 37 C.F.R. §2.56(b)(5).

Sometimes, the owner/certifier prepares tags or labels that bear the certification mark and that are supplied to the authorized users to attach to their goods or use in relation to their services. See Ex parte Porcelain Enamel Inst., Inc., 110 USPQ 258 (Comm’r Pats. 1956). These tags or labels are acceptable specimens if they are shown affixed to the certified goods. Cf. 37 C.F.R. §2.56(b)(1)-(2). A label or tag that is not shown physically attached to the goods may be accepted if, on its face, it clearly shows the mark in actual use in commerce. See TMEP §904.03(a) for more information regarding unattached labels or tags.

See TMEP §1306.04(c) for information regarding characteristics of certification marks and specimens that show the mark functions as a certification mark and §1306.05(b)(iii) regarding specimens for geographic certification marks.

Under 15 U.S.C. §§1051(b), 1054, and 37 C.F.R. §2.45(a)(4)(ii), to establish a basis under §1(b) of the Trademark Act, the applicant must:

Prior to registration, the applicant must file an allegation of use (i.e., either an amendment to allege use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(c) or a statement of use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(d) ) that states that (a) the mark is in use in commerce and (b) the applicant is exercising legitimate control over the use of the mark in commerce, includes dates of use and a filing fee for each class, and includes one specimen evidencing such use for each class. See 37 C.F.R. §§2.76, 2.88. See 37 C.F.R. §2.76 and TMEP §§1104–1104.11 regarding amendments to allege use and 37 C.F.R. §2.88 and TMEP §§1109–1109.18 regarding statements of use.

Once an applicant claims a §1(b) basis for any or all of the goods or services, the applicant may not amend the application to seek registration under §1(a) of the Act for those goods or services unless the applicant files an allegation of use under §1(c) or §1(d) of the Act. 37 C.F.R. §2.35(b)(8).